- JP

- EN

Ay-O Oral History

Interview with Ay-O, June 28, 2014

Place: Ay-O’s Studio in Namegata, Ibaraki Prefecture

Interviewers: Yarita Misako, Kakinuma Toshie

Translator: Akimoto Shinobu

Ay-O (b. 1931)

Artist

Born in Namegata, Ibaraki Prefecture. In 1958, Ay-O left Japan for the U. S., participating in the international avant-garde art movement Fluxus. He drew attention with tactile art works “Finger Box” and “Rainbow” series in which the entire color spectrum was painted in gradation. In April 2014, he was involved in “Fluxus in Japan 2014” held at Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in which he realized his own performance works by himself. With poet Yarita Misako who has known the artist for years, we interviewed him for our oral history archives on his activities in the U. S., the idea of Rainbow, silk-screen prints that produced multiple works, and collaboration with other Fluxus artists.

Oral History Interview with Ay-O

Kakinuma: Today is June 28, 2014. We are speaking with Mr. Ay-O in his studio. The interviewers are, poet, Ms. Yarita Misako, and myself, Kakinuma Toshie. Shall we start?

Ay-O: Today’s June 28… Saturday, isn’t it.

Kakinuma: It is. I just saw “Fluxus in Japan 2014” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, which you are a part of. You did your performances and saw other members—how did that feel?

Ay-O: Saw who?

Kakinuma: Ben Patterson, Eric Andersen, and your other Fluxus peers from that time—how was it?

Ay-O: Well… [laughs] It’s like that, really. [laughs]

Kakinuma: I watched your three performance pieces. One was Morning Glory (1976), of “brushing teeth”, and one was Ha Hi Fu He Ho (1966), on laughing, and the other was 07th. Is it “O-seventh”?

Ay-O: It’s “Zero-seventh.”

Kakinuma: These three performances I saw have hardly been mentioned in lists of your artwork. First, I would like to ask you about Morning Glory; do you remember when you first performed it?

Ay-O: No I don’t! I don’t remember! [laughs]

Yarita: I think I’ve seen it among works by Fluxus in New York.

Ay-O: You know, “Morning Glory” is “Asagao” [in Japanese]—“Morning glory / Climbing up the well-bucket / I ask for water from the neighbor” [a haiku by Fukuda Chiyo-ni]—that’s it, that’s just it.

Kakinuma: You’ve also done the tooth-brushing performance in [Karlheinz] Stockhausen’s music theater Originale; is that the same thing?

Ay-O: It could be the same but could be different. [laughs]

Kakinuma: Could we say that’s the origin of this piece?

Ay-O: Well… I don’t know.

Kakinuma: Can you tell us about Ha Hi Fu He Ho then? It’s a performance in which you laugh. I saw the one you did with Mr. Tone [Yasunao] on the Internet, where three of you were laughing—perhaps in New York?

Ay-O: That was with my friend Emmett Williams—both of us were fascinated by humor. That was it; we were just interested in humor.

Kakinuma: Do you remember when you first performed it?

Ay-O: Not really… You know, humor can be expressed in “ha hi fu he ho”. At different places and times, I attempted to dissect it or experiment with it, and that was my performance. There’s a painting as well, on a large canvas.

Kakinuma: A painting of Ha Hi Fu He Ho! Is it painted in rainbow colors?

Ay-O: It has the letters—ha, hi, fu, he, and ho.

Kakinuma: In black?

Ay-O: No—it was in my exhibition, though.

Kakinuma: Was it?

Ay-O: It was, wasn’t it?

Ikuko Iijima [Ay-O’s wife]: It’s in the catalogue.

Yarita: It’s in the 2012 catalogue from The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo [MOT].

Ay-O: That is a really old catalogue. [laughs]

Kakinuma: This one is from 2004—the catalogue from Urawa [Art Museum].

Yarita: It should be in the MOT catalogue.

Kakinuma: So, Ha Hi Fu He Ho was originally a painting and there’s a performance version of it?

Ay-O: No, not like that. There was a thing “on humor”, which was… what do you call it, that we did in Karuizawa?

Ikuko Iijima: A seminar “On humor.”

Ay-O: We organized a seminar called “On humor.” [Aug 23–28, 1976, at the Shiga Kogen Hotel] Emmett Williams and I were lecturers and five or six people gathered. Where was it?

Ikuko Iijima: Wasn’t it in Shiga Kogen?

Ay-O: Right, at Shiga Kogen Heights. Is it a hotel? What are those called?

Kakinuma: Not a hotel?

Ikuko Iijima: Maybe it’s called a “hutte”? [** German word for a chalet]

Ay-O: It is kind of a hotel, where we all stayed. Emmett and I acted as instructors and put on various performances.

Kakinuma: I see, and that’s when you performed Ha Hi Fu He Ho?

Ay-O: Even before that, I had always wondered about humor; what it is. I wanted to clarify it through different experiments. In Japanese, the letters “ha hi fu he ho” represent humor—hahaha, hihihi, fufufu, you know.

Yarita: They are the sounds that release so much breath.

Ay-O: That’s right. So I brushed my teeth for the sound “ha.” [laughs] [Note: The Japanese word for teeth is “ha.”] And brushing teeth for “ha” is a pun on the Japanese classic: “Morning glory / Climbing up the well-bucket / I ask for water from the neighbor.” It’s simple—just an association; therefore the title, Morning Glory. Then after that was born, I attached other actions to the sounds “ha hi fu he ho” and developed the performance.

Kakinuma: So, for instance, is there something for “hi”? If “ha” is brushing teeth, what is associated with “hi”?

Ay-O: For “hi”? Yes, there’s something for “hi” as well. There are actions paired with all letters.

Kakinuma: For all of them—what is for “hi” then?

Ay-O: I can’t remember. [laughs] But there are.

Kakinuma: There are performances for all of them—I see. So both performances you did last time meant something specific.

Ay-O: I suppose so.

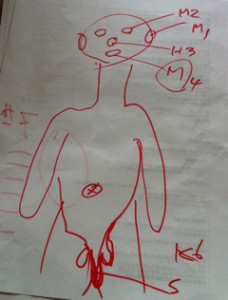

Kakinuma: All right, then how about the other work, 07th—what does this title imply?

Ay-O: As in the Finger Boxes [c. 1963] and other works, I have a patent on holes. [laughs] So I have many ideas about the holes on 07th.

Kakinuma: Is “zero” a hole?

Ay-O: Look, there are seven holes here.

Kakinuma: And different things come out of the holes?

Ay-O: Not really. That idea came afterwards. It’s more about the exploration of holes.

Kakinuma: What does 7th stand for? Does it mean there are seven holes?

Ay-O: This first hole is an ear.

Yarita: Ah, it’s a human body.

Ay-O: This is an eye. This one is a nose.

Kakinuma: A nose.

Ay-O: If we keep going like this, we won’t finish it until next year, will we? [laughs]

Kakinuma: Well, that’s true; could you explain it briefly?

Ay-O: Briefly? It can’t be brief since I’ve been doing it over 60 years. [laughs]

Kakinuma: I suppose not.

Yarita: It’s been a long exploration.

Ay-O: This is a nose, and a mouth. One, two, three, four. This one is for peeing, a urethra. And here’s an anus, that’d be six. The anus is the sixth. So one more… a birth canal? What is it called?

Kakinuma: That’s a birth canal [vagina]—for women.

Ay-O: There you go, a total of seven. That’s what 07th stands for.

Yarita: Wow! The openings of a human body; the holes connected to the world.

Ay-O: Sometimes, when I’m just thinking about holes all day or for 10 days straight, I get many ideas. That’s how 07th came about.

Kakinuma: I just saw your sculpture with the mouth open over there—things go into the hole as well on that one?

Ay-O: That, if something goes in, it comes out from here; the real thing comes out. But kids, brats shoved stones in and clogged it. [laughs]

Yarita: It got constipated [laughs]—that’s too bad. There’s also a smaller bronze one, I believe?

Ay-O: That one, you pour rice in and it comes out.

Yarita: Audiences put rice in and it slips out of the bottom.

Ay-O: This, 07th, is a woman. A man should be 06th—one hole missing.

Yarita: I guess it’s related to the image of birth, that different things come out of a hole? Like a baby is born?

Kakinuma: Did you first perform 07th in New York?

Ay-O: Yes, as I had always created work in New York, and also performed in New York.

Kakinuma: A different thing comes out every time?

Ay-O: Yeah, well, it should be—as we eat a different thing every time. [laughs]

Kakinuma: At the performance, you scattered instant coffee on the stairs, not coming out of a hole. I could really smell the coffee.

Ay-O: That, we really should have scattered it in the gallery but they were hesitant, like, it’ll be messy. I would have done it in the past—I would scatter it no matter how clean the space was.

Yarita: Why not stimulate the five senses? Art should not be just seen; it should be heard or felt as well.

Ay-O: I’ve even sprinkled water with a funnel.

Kakinuma: Colors, too; there was shaving cream, ketchup—many different colors came out.

Yarita: The colors were amazing. So many colorful balloons as well.

Kakinuma: I really enjoyed it.

Yarita: It was exciting, wondering what would come out next.

Kakinuma: With anticipation.

Yarita: We were really anxious to see what trick Mr. Ay-O would come up with next—it was so much fun.

Kakinuma: I felt like a child watching it.

Ay-O: Definitely—there’s no difference. It’s the same feeling.

Kakinuma: It was quite playful.

Ay-O: A child’s mind is the best. If only we could all go back to that state, we’d be able to create something most authentic.

Yarita: If we can feel fresh about everything, we would be happy just looking at the sky, clear or cloudy.

Ay-O: The “first times” in life… Oh and, there’s a belly button, here.

Kakinuma: A belly button is not a hole though.

Ay-O: It used to be a hole.

Yarita: We all used to be connected to the birth canal while in our mother’s womb, even a male. So if we consider a belly button and a birth canal [vagina] together, that could be the 7th hole for a man as well, no?

Kakinuma: I see, so it could be a man as well.

Ay-O: I suppose so. That’s art, such non-sense. [laughs]

Kakinuma: Now, we’d like to go back in time and ask you a bit about the time you moved to New York. Do you have any questions, Ms. Yarita?

Yarita: One of your stories that stays in my mind is that when you first went to New York, no galleries showed interest in you. You said you visited all of them to introduce your work.

Ay-O: I did. There were 140–150 galleries in New York, and no one wanted me. [laughs] I tried it three times.

Yarita: Three times. Visiting 150 galleries three times means that you approached 450 galleries.

Ay-O: Yeah, and sometimes, I would roll up and bring a large piece, as big as this room.

Yarita: And every single gallery said “No”?

Ay-O: They all said “No.”

Yarita: But you must have been confident in your work, as you were somewhat established in Japan?

Ay-O: Sure, I didn’t go there to study painting; I went to market my work, something new for them, you know.

Kakinuma: But then…

Ay-O: No one wanted it. [laughs]

Yarita: Those who are not ambitious enough would get disheartened and come back at that point but you kept going.

Ay-O: Of course I was crushed, too—every time. [laughs] It was miserable.

Yarita: There was a period you painted an X over your paintings?

Ay-O: When I visited these 150 galleries, they’d tell me, “These are the painters we represent.” They were all abstract action painters back then—nothing else.

Yarita: That’s when Jackson Pollock was popular?

Ay-O: Yeah, unless you were Jackson Pollock, you were no painter.

Yarita: Wow, it was a fad, I guess.

Ay-O: Not just back then, it’s always like that everywhere—even now. There’s always a trend; it’s common.

Yarita: So then you made action paintings as well?

Ay-O: Yeah I did, or no one would care. They’d say to me, “Our painters are like this” as though telling me to do the same. So I was doing this and that for about two years.

Yarita: You even tried out action paintings but…

Ay-O: Well, after all, I gave up and started action painting. I’d stretch the canvas on the floor in my apartment about the size of this here, and drip paint over it.

Yarita: In the New York School style.

Ay-O: I painted as an abstract painter. After mixing the paint and splashing it on the canvas, I couldn’t stay in the room. So I’d get out and head to Times Square, and watch, say, three cheap movies. Three double bills, so six movies in total.

Kakinuma: To clear your mind?

Ay-O: Not really. [laughs]

Kakinuma: No?

Yarita: Just to let the paint dry and avoid the fumes of turpentine.

Kakinuma: Ah, for that.

Ay-O: It really stinks—you could die.

Yarita: You start hyperventilating—it must be like chemical poisoning from the fumes. So you went out to avoid it and kill time.

Kakinuma: And waited for the paint to dry.

Ay-O: Turpentine is the same as gasoline.

Yarita: So you’d watch six movies and come home and look at your painting, and then…

Ay-O: When I left Japan, I swore that I wouldn’t copy anyone—but I did, after all, and that really upset me because I was lying to myself. So I’d start an argument and everyone would fight back if I instigated it. Then after a while, I realized that I was speaking English pretty well. [laughs]

Yarita: Arguing helped you to practice English.

Kakinuma: They say you are fluent in a language if you can fight in it.

Ay-O: It’s the best way to learn a language, because in a fight, you’re only saying what you want to say.

Kakinuma: What happened after that?

Ay-O: I got fed up with myself and crossed out all my New York School style action paintings. They’re in here, with Xs.

Yarita: I heard that you destroyed some of them, though we can still see many of them in your retrospectives. You also said that you became conscious about the quality of the Xs as well.

Ay-O: You know, I am a painter after all—so while putting an X on my painting, I would say to myself, “well, this one isn’t good enough.”—even about the way I cut the canvases. Anyway, that’s what happened, crossing out all my paintings like a dead end—huge Xs all over the apartment. My canvases came from discarded or half broken paintings that I’d peel off and cover in white to reuse.

Yarita: It may sound better if we call them “recycled”, but they were simply second hand canvases.

Ay-O: I’d paint four or five of those a month. After about 20 or 30, I’d do all kinds of things to them. An X wasn’t good enough so I’d burn or bake them.

Yarita: That was your main tenet, that you wouldn’t repeat or copy others.

Ay-O: Well, most of us copy others anyway, painter or otherwise. Musicians and other professions do it, too. If you are determined not to copy others, then you really have to come up with ways to avoid it—it’s not easy.

Yarita: If you don’t want to look like Van Gogh or Cezanne, you must search for your own motif or style somewhere else.

Ay-O: So I decided to tear up all my old paintings, and thought over what I could do with them. Then I just lined them up and there appeared a room. They became a funny-looking ragged house, which I turned into artwork.

Kakinuma: Is that Tea House [c. 1961]?

Yarita: I’ve seen your small huts made of fabric like that.

Kakinuma: That piece also has holes in it—maybe it’s not listed in this catalogue, I wonder. It’s in your own catalogue but may not be in this Fluxus one. Anyway, so now you created Tea House.

Ay-O: It turned out like that. Then all these unconventional artists came to see it—they were eccentric friends, who came. I was making work like that back then.

Yarita: And then, those painters and artists who were not represented by New York galleries started gathering around you and interacted with each other.

Kakinuma: Did Yoko Ono also come to see Tea House?

Ay-O: She did.

Yarita: Yoko, Ushio Shinohara, and On Kawara as well. There must have been some other artists from Japan, too. Was it through Yoko Ono that you connected with Emmett Williams and George Maciunas?

Ay-O: I think so—this strange bunch of friends would get together and organize group exhibitions and so on. If someone initiated a performance, others would also do performances, including myself. It was all like that—an odd group. But it wasn’t that we were copying each other; these things just happened simultaneously, all over the planet. What’s curious was when you had no choices left as an outsider, everyone acted similarly. It happened all at once—it was like, I did this but someone else was also doing similar stuff. When you went to see it, you’d figure it out, “Oh this is why that came from that.” You’d totally understand these eccentric “happenings” so you could even contribute to them.

Kakinuma: You met Maciunas around that time?

Ay-O: I was still looking for a space for an exhibition and someone introduced me to him. Maciunas wasn’t an artist, but he had a gallery.

Kakinuma: Was that the AG gallery?

Ay-O: It was the AG gallery.

Kakinuma: And, someone took you there.

Ay-O: Yeah, I showed photos of my work and said, “I want an exhibition”; then George goes, “You have it,” and told me to come back in two or three months to discuss details. So I went back but there was no gallery; he was up to his neck in debt and fled to Europe.

Yarita: He left for Germany, right?

Kakinuma: Why was he in such debt?

Ay-O: He was a commercial designer and making good money, $1,000–$2,000 a month.

Kakinuma: Then why?

Ay-O: He spent too much on people like myself—organizing unusual exhibitions for eccentric artists.

Kakinuma: He used all his money for that?

Ay-O: He had no way out and escaped to Europe. One of the reasons he went to Europe, George told me, was that he wanted to sell that red book, Anthology, compiled by some in our group. I wasn’t part of that though. Anyway, nothing sold.

Kakinuma: It’d be worth so much money now! [laughs]

Yarita: Really expensive…

Ay-O: He took the books with him to sell—but since no one came to see them, he thought of something different to attract an audience. He had youngsters play music all over the place, like in Germany.

Kakinuma: Didn’t he organize the first Fluxfest in Wiesbaden?

Ay-O: He did them all over the place.

Kakinuma: Right. I find it curious that it was a music festival but not an exhibition.

Ay-O: Yeah, it was a concert.

Kakinuma: Isn’t it interesting it was a concert.

Ay-O: There were many musicians in the group—as musicians, they spoke in music language through a concert, you know. It’s perhaps similar to artists having an exhibition, but probably, there weren’t many visual artists per se. There was [Claes] Oldenburg, a Swedish artist; he was also engaged in “happenings” quite a lot and became famous in no time.

Kakinuma: Anyway, after that, George Maciunas returned to New York, I guess?

Ay-O: He organized exhibitions and concerts under the name Fluxus and when he came back, he set himself up nearby. It’s in here—not an exhibition but…

Kakinuma: The YAM festival?

Ay-O: There was something before YAM that our New York peers organized. That was a separate thing.

Kakinuma: It says in here that you did something called the Hat Show [The YAM Festival Hat Show].

Ay-O: We decided to put on a hat show at an exhibition, so everyone brought a hat.

Kakinuma: So that’s when you wore a hat like this? Or it’s different.

Ay-O: In America, on April something, when people wear hats and wander around…

Kakinuma: You mean, Easter?

Ay-O: Is it Easter that people wear hats? So that’s when the idea for the exhibition with hats came up and we organized different things.

Yarita: All these unique ideas…

Kakinuma: Yeah, really. You then paraded wearing hats?

Ay-O: Um-hum, on top of the gallery exhibition.

Kakinuma: Then Maciunas proposed to open a Fluxus shop—not a gallery but a shop.

Ay-O: He had split but then returned to New York and contacted me. I think it might have been his last time in New York; maybe he moved abroad again after that, I’m not sure. Anyway, he came to me and said he wanted to open a shop, not a gallery, and sell our work there. So I said “OK,” and he rented a warehouse—it’s called a “loft.”

Kakinuma: And it was around the corner from your place?

Ay-O: Yes it was; I was living in one of them. They were called lofts whereas in Japan, they are ateliers. That’s where I worked too.

Yarita: They do look like warehouses in the photos from that time.

Kakinuma: Is this where the shop was? There’s a Fluxus flag.

Ay-O: Yeah, that’s it. Mine was this one, two doors down. I had various power tools there; a drill was only $50 back then. It wasn’t possible to buy a drill or a saw for $50 in Japan. So I got so excited I bought it, and would make holes in a huge aluminum piece. Then that became an artwork—you know Canal street; junk like that was sold right there.

Kakinuma: And then the orchestra concerts also began?

Ay-O: George came and asked if the space next to me was available to rent. I divided the space into three, the front for a Fluxus concert hall, the middle for a gallery, and the back for his bedroom—free labor.

Yarita: Like Do-It-Yourself?

Ay-O: Carpentry was my part time job. I had all kinds of jobs but the one you have skills for brings the most money in the end. That helped me to buy and learn to use more power tools, so we started a business. George would find clients and we’d make things.

Kakinuma: Did you sell them?

Ay-O: As he was a designer, he worked for commercial spaces who wanted to have shows for advertising.

Kakinuma: To attract customers?

Ay-O: Exactly. He’d bring that kind of job and show us sketches of how it should look. We were the labor—my friend and I would build things for the clients George had found and he’d pay us.

Yarita: So the Fluxus members all had roles, those who found customers, who made things, and who performed.

Ay-O: I suppose.

Yarita: Did you start making rainbow paintings around then?

Ay-O: Yes.

Yarita: How did you come up with the idea?

Ay-O: I’ve told you that I had decided not to copy others, so I had to think about what I could do otherwise. Even I do a little thinking. [laughs]

Yarita: As a result of a lot of contemplation and struggle. [laughs]

Ay-O: I pondered this—how I could make authentic work without copying others, making the most of my own sensitivities. You know we have [five] senses, and a sixth sense—taste, hearing, sight, smell, and touch—tactile sense. I wanted to explore each one of them as much as I could—I’m just a university graduate and not really an expert on it, but I tried to apply as much knowledge as I had in order to do this.

My family’s business did not thrive.

Yarita: Was your father the heir of the Iijima family?

Ay-O: My father was the second oldest son of the Iijima’s—my family name. The oldest son inherited the name. My father was a soldier and when he came back [from World War II] he helped on the family farm—he liked it though.

Kakinuma: Was he a pilot?

Ay-O: Yes he was; a pilot for the Navy.

Kakinuma: Were you born here, too?

Ay-O: Yeah, as this was my father’s property. He had only one brother—when his brother died, my father asked me to help around the farm but I refused and left. What could he do, his son disappeared to America. But then my father also passed away and because my uncle had been gone, I became the heir after all. At that time in Japan, they implemented a law limiting the size of the rice paddies one family could own, and I got both my father’s and uncle’s share. [laughs] There were vegetable plots as well—I just didn’t do anything with them.

Yarita: All around here is the Iijima family’s land?

Ay-O: The rice paddies are. There are some below and above here—three large ones. We have quite a few vegetable plots as well—they are all rented. I really don’t know much about it.

Kakinuma: Ok, shall we go back to the interview?

Yarita: Yes, so now, you’ve discovered the rainbow and started painting it—you were talking about your senses, and a sixth sense.

Ay-O: Right, I felt an urge to explore my senses and a sixth sense, and I started it. One day I had an exhibition of the work I had been making using sponge. Someone who came to see it asked me if I was the artist, and whether I wanted similar foam rubber, so I said, “sure.” A couple of days later, a huge truck pulled up under my apartment on Canal street, and this big black guy kept bringing all this foam up into my apartment on “two flights up”, actually on the 3rd floor—in New York, people count floors like that; one flight up, two flights up. He delivered it all, all by himself, until my apartment was filled with foam rubber. I was broke and had to use whatever was available to make work. So I thought: “This may be good for the work about touch,” and made the Finger Boxes.

Yarita: This piece here was made before the Finger Boxes, wasn’t it? Big sponge pieces like this one eventually developed into the Finger Boxes, just because you were given lots of materials.

Kakinuma: Were the foams that big?

Ay-O: Somehow they were—as big as this room. I guess foam rubber has hard sides that are chopped off. They only use the middle part. The ones given to me were the hard sides they had cut off.

Yarita: Like the ends of a sponge cake.

Ay-O: So I used them for about a year. I made huts or rooms you can go into.

Kakinuma: Oh, I get it; they turned into those…

Ay-O: And that created a buzz, like, “this guy’s making weird things.”

Yarita: There was a lot of art and music but you were the first artist who surprised people by art you had to touch, no?

Ay-O: Sure, no one else had done that.

Yarita: The Finger Boxes are fabulous. Has anyone accidentally hurt himself with the thumbtacks?

Ay-O: Well, there were some incidents—but anyway, there they were, the Finger Boxes. I could make anything in my wood shop—it’s just that I had fun making them and not that they sold.

Yarita: The big boxes that house the Finger Boxes are all very pretty, too, and those branded with your name are also beautiful.

Ay-O: When I start something, I have no idea where to begin, so I begin with a consideration of the tactile aspect—everything has a specific feel after all.

Yarita: That’s true—it’s cold or hot, hard or soft and so on.

Ay-O: I felt I should compile such a collection.

Yarita: You tried to examine all these sensations, I suppose.

Kakinuma: Your “Tactile list” is included in John Cage’s Notations [New York: Something Else Press, 1969]. It lists things like sand, mink, and water—things that all feel different. What motivated you to create this list?

Ay-O: Well, if I claimed to be at the vanguard of this, I’d have to set a precedent and therefore I made a list.

Yarita: You listed physical sensations, things that evoke tactual experiences.

Ay-O: Um-hum, I made a list of cold, hard etc.—since the objective eventually becomes your own experience, these observations are really important for humans, to ultimately consider how we perceive or handle these elements.

Kakinuma: There were 15 original Finger Boxes?

Ay-O: I don’t think that’s right—all of these. There were many.

Kakinuma: There are 40 items in here [in the Tactile List]

Ay-O: There should be more, about 100—from all objects.

Kakinuma: That’s true, because all have different sensations. Oh, OK, I get it, you did not make these 40 into boxes.

Ay-O: Each box contains a different texture but the Finger Box [Kit] is a set of them—a “tactile set.”

Yarita: Some are a set, and others resemble a room.

Kakinuma: There are ones like a room as well?

Ay-O: Not everyone would go about it this way. I just brought all these together and made this and that, and assembled them as a kit—all for my own amusement.

Kakinuma: This was conceived in ’66.

Ay-O: Earlier than that, maybe in ’63.

Kakinuma: That’s early. It’s around the time Fluxus emerged.

Yarita: As Mr. Ay-O has said earlier, Fluxus was not a kind of school, unlike the way Japanese people think; but rather, it was more that, while you were having fun making the Finger Boxes, Nam June Paik was also doing his own stuff in Germany, all outside of conventional art practice—I feel that it was perhaps a bit of a counter-reaction against the pre-war culture as well?

Ay-O: You know it’s funny; there were artists like me, or Paik, who started sprouting like bamboo shoots around the planet all at the same time.

Kakinuma: It’s really fascinating.

Ay-O: Yeah, it really was intriguing. It’s not that we copied each other but you’d hear about these novel endeavors and when you went to see them, you’d realize that they were doing the same sort of stuff as yourself—you felt like comrades and helped to promote each other.

Kakinuma: Ms. Shiomi [Mieko] too, was making work like her Endless Box (1963) without knowing Fluxus. Then Paik said to her that her work was Fluxus, which made her decide to go to New York—it’s compelling.

Ay-O: It is, and it happened everywhere. In communist Soviet Russia as well.

Kakinuma: In Denmark, there was Eric Andersen.

Yarita: Those who rebelled against the established art market, where money and authority determined the value of art, sought a new art movement, perhaps.

Ay-O: Sure, everyone wanted dollars. [laughs]

Yarita: Of course they did but…

Ay-O: If we could sell work, that would’ve been best but because we didn’t…

Yarita: So, did you also begin the rainbow paintings when you were making the Finger Boxes?

Ay-O: Oh, right, we haven’t reached that point yet. [laughs]

Yarita: Sorry, I’ve been looking forward to the rainbows.

Ay-O: Not at all! You know, I liked analyzing things. Since I started as a painter, I was more knowledgeable of color than other people. So I contemplated color and thought I’d paint based on that. It just began like that, but no other painters were approaching painting as I was.

Yarita: Analyzing color—if you think of the essence of color, it’s the light that makes it visible, isn’t it?

Ay-O: Indeed. Things like that, we all study at the university and art school. Everyone knows it—common knowledge. That’s the only area that I knew more than the average person. Back then, many artists rigorously researched and explored color, particularly commercial artists. I’d apply this knowledge or do various experiments with color too. Ultimately, colors are endless—if you mix 24 colors, they become 48; they double forever and are hard to organize. So I needed a concept to arrange them and the idea of a “conceptual” approach came about. The notion of “conceptual” was what Fluxus artists shared. I myself approached color totally conceptually, but it wasn’t for everyone. Then gradually “conceptual art” appeared; some of our peers championed “concepts as art”, or they claimed that one must pursue concepts in art and so on. It became a fad and so, I was considered a “god.” [laughs]

Yarita: You first thought about a concept of color.

Ay-O: Not just as color, but as something conceptual.

Kakinuma: You had mentioned that you used dice to decide what color or color combination to use—is it true?

Ay-O: Sometimes. Not just with dice, but anything. By writing numbers on chopsticks, like divining sticks.

Kakinuma: As in fortune telling.

Ay-O: Yes, by pulling a numbered stick to choose a color—that one in front of us was made like that.

Kakinuma: In that way, wouldn’t color combinations be irregular unlike that painting?

Ay-O: Yeah, they’d be all mixed up.

Kakinuma: Did you ever use, for instance, a computer for the same purpose?

Ay-O: You wouldn’t need a computer.

Kakinuma: Oh, I see. Well, I just thought of how John Cage used it. He digitalized the I Ching to select combinations of notes, but I guess you didn’t?

Ay-O: We have dice to decide on things, you know. All my friends, Americans they were, read the book I Ching. When I went to France, George Brecht and Robert Fillou were living together; they were so into I Ching. I asked, “Why are you guys reading such a thing?”; they said, “This is an amazing book.” To me, it was just a fortune telling book.

Yarita: Yeah, for Japanese, it is.

Ay-O: But if you look at it closely, I Ching is interesting. Japanese are able to understand the original concepts better than Americans; so after I read it, I immediately began using it for my work.

Yarita: A variety of elements started coming together. The rainbow as well, the rainbow is composed with light…

Ay-O: For me, color is the rainbow, the spectrum. Humans conceived of the spectrum as stages of color, from red to purple. It’s color theory but if you explored it thoroughly, you’d figure out how to apply colors. I understood it better through analyzing than painting. You know Picasso painted only in blues at one point, for about five years.

Kakinuma: The blue period.

Ay-O: There was the blue period and the pink period. He didn’t sell much during the blue period but in the pink period, he started doing OK. Then the work from the blue period began selling as well. Those were the only times Picasso sold his work—he did not sell that much all together.

Kakinuma: Is that so?

Yarita: Not when he was young. Mr. Ay-O, you explored the spectrum of visible light, the seven colors in the rainbow, in many different ways. For instance, you thoroughly broke them, right down to—192 colors, was it?

Ay-O: “24, 48, 96, 192”—these are scores in mahjong. I could actually make this many colors myself. At one point, that was all I did for about two years; I’d simply apply one color a day, to make a painting of 192 gradations.

Yarita: You had to wait for the previous color to dry before putting a new one, or they’d smudge.

Ay-O: A bit silly, it was.

Yarita: But it was also a pursuit.

Ay-O: Really, you have to actually do it. A theory alone won’t do; but not everyone does it even if they have a similar idea. That just doesn’t work; you’d only discover something new by doing it. So I did—I couldn’t get drunk while making a 192-color painting.

Kakinuma: You couldn’t?

Ay-O: If you are drunk, or hung-over, it’s no good. So I tried not to.

Kakinuma: You had to take care of yourself—you mean unless you were totally clear-headed, you could not produce different colors?

Ay-O: It’d be no problem if I were making 24 colors. Even 48 or 96. But when it’s 192, there’s almost no difference between colors. You have to make a gradation based on the color from the day before, so if you failed at one stage, there’s no next stage—you couldn’t be hung-over. [laughs]

Kakinuma: I don’t know much about visual art, but you moved onto printmaking after painting.

Ay-O: I was actually making prints right from the beginning.

Kakinuma: You were doing both?

Ay-O: Printmaking [hanga] was looked down on. It’s written as “half a painting [hanga].”

Kakinuma: They say it’s half-baked.

Ay-O: I’d argue, “That’s nonsense, a print and a large canvas have the same value,” and get into a fight because of my combatant nature.

Kakinuma: What I thought interesting was in the past, say, for Ukiyo-e prints in the Edo period, there was a painter, a carver, and a printer, dividing the labor. In your case as well, I believe you are the painter and you employ a printer separately?

Ay-O: Yes I do. Printmakers nowadays create what’s called “Sōsaku-hanga.” [**Prints devoid of editioning made by solely one artist] They make one print, study it, and make another with new colors—they are expressive, but I don’t do that.

Kakinuma: That means they only make one print, doesn’t it?

Ay-O: Well, not necessarily. For example, if you could make 192 colors of paints, you’d have to think of ways to make them, and then make a painting…

Yarita: Because you have a concept for making the original image, serigraphy or printmaking is an appropriate medium to reproduce the work—isn’t that what you mean?

Ay-O: That’s right.

Yarita: In other words, if one’s work is expressive, you may not be able to reproduce the image accurately in printmaking, while a conceptually conceived work is easier to reproduce—am I right?

Ay-O: Yes, you’re right. I think that’s it. Few artists create work in such a way though—they’d say, “This color doesn’t seem right” and would change it. I don’t—if I planned to make a painting with 24 colors, I’d put a color, and then another color, and when they are all laid down, it’s finished—whether I like it or not.

Yarita: That’s why printers get it right. It’s not your expression but your concept that makes up your work and if the printer understands it, he can reproduce it accurately. Your printer for serigraphy is Kenryo Sukeda from Fukui—have you worked with him for a long time?

Ay-O: He still prints my work. There was also Okabe [Tokuzō], but he passed away.

Yarita: Mr. Okabe was well known, too.

Kakinuma: How many editions do you make for one image?

Ay-O: I was already making prints even before I moved to the States—initially lithography, then etching; I did not do woodcuts but did copperplate engraving…

Yarita: There are quite a few people in Ōno associated with Fukui’s Sōbi [The Association for Education through Creative Art], who have purchased your screen prints; they really treasure them, like a family heirloom. Those who lived in rural areas and had few chances to go see art could appreciate your original art through the etchings and screen prints, and perhaps, their sales supported your practice in New York—could we say that there was a mutual benefit?

Ay-O: Certainly. You know, a painting is one of a kind and reproducible prints are cheaper and less profitable, they say, but I disagree. If you produce more, more people can have them. If you produce ten not just one, you can sell them less expensively and more people might be able to afford them. I think that’s really important.

Kakinuma: Fluxus artists often made multiples; does it relate to printmaking?

Ay-O: They are the same thing, prints and multiples are—plural, plurality.

Kakinuma: To make multiples means there is not only one work, right?

Ay-O: It fundamentally denies art from the get go.

Kakinuma: It denies the idea of the original, or one of a kind.

Ay-O: It does—it’s ultimately a different kind of art. My musician friends might have had some influence. Musicians compose music, but artists could make music too, and the score you wrote can be played multiple times. Printmaking allows you to make the same image more than once. It automatically rejects “art for art’s sake” [or Aestheticism].

Kakinuma: I would like to ask you some music-related questions. After you met Maciunas through Fluxus, you two had argued about whether to perform Stockhausen’s Originale. But in the end, you participated in the performance?

Ay-O: That was Paik, who initiated it, since he was working with Stockhausen in Germany. He wanted to perform Stock[hausen]’s piece but as Stockhausen was a renowned musician, you know, during the war….

Kakinuma: There were people who accused Stockhausen of being an imperialist.

Ay-O: A militarist.

Kakinuma: That caused a protest?

Ay-O: Some Americans were naïve, frankly. They’d write about past work Stockhausen had done for the Nazis and so on, and we’d respond, “We won’t do that.”

Yarita: Americans are not fond of Communism, let alone Nazism, and some are quite sensitive and hostile towards that kind of thing.

Ay-O: You know, it’s hard to avoid it when you are famous. In Japan as well, once you get recognized and are asked to write a song to glorify the nation…

Yarita: And if you made a nationalistic work, you are accused of having supported the war.

Ay-O: Precisely.

Yarita: That happened in all countries at one point.

Ay-O: Everyone goes through it. The better known you become, the more you are targeted—particularly if you are a good artist.

Yarita: In Japan, Léonard Foujita [Fujita Tsugouharu] was accused of making war paintings. He got fed up with it and never went back to Japan.

Ay-O: I know what happened. Mr. Foujita returned to France via America.

Yarita: He traveled around the world before going back.

Ay-O: I knew the person who invited him to the States—a Japanese. It was a big deal.

Yarita: Mr. Foujita’s Battle of Attu (1943), for example, depicted the suffering of the people during the war rather than glorifying it, but he was terribly criticized.

Ay-O: Well, but even if it wasn’t glorifying the war, it hurt some people.

Yarita: I guess we can say anything after the fact.

Kakinuma: So now, you performed in Originale, in the role of a sculptor?

Ay-O: Paik brought Stock[hausen]’s Originale and suggested that we perform it—he told me that my role was “the sculptor” right from the get go. Stock had composed it for his wife, Mary Bauermeister—she was an artist who used magnets in her work.

Kakinuma: So you were told to play the sculptor.

Ay-O: Yes, to play the sculptor; but then right away, George Maciunas objected to it. I didn’t want to fight over something like that, so I said, “I won’t do it.”

Kakinuma: So then what made you be in it after all?

Ay-O: It was Allan Kaprow who arranged it. Paik let Kaprow organize and direct it. I knew Kaprow and he told me that he was directing it—so I took the part of Mary Bauermeister after all; I could perform any of my pieces I wanted in it.

Kakinuma: Oh I see, that’s why you did the tooth-brushing performance in it, or shaved your beard?

Ay-O: That’s right.

Kakinuma: Were they specific to colors, like, you shaved your beard for red, brushed your teeth for orange? They were associated with colors?

Ay-O: Well, they were—they were intricately connected. Music is ultimately time and time can be simply conceived through the rainbow colors—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, purple. Starting with red, you can use all these colors.

Kakinuma: So you used seven colors.

Ay-O: Whether seven colors or more, they can be applied to time, so that’s why I used them.

Kakinuma: Then after that, Mr. Takemitsu [Tōru] composed Seven Hills Events for Ay-O (1966)?

Ay-O: No, it wasn’t that, it was, umm…

Kakinuma: He dedicated it to you, didn’t he?

Ay-O: Right.

Yarita: It was re-performed at MOT in 2012, wasn’t it.

Ay-O: Ah, that was great—didn’t you think it was good that it happened?

Yarita: Absolutely.

Kakinuma: I missed it; did you see it?

Yarita: I did. Aki Takahashi was there of course; so were Mr. Ichiyanagi [Toshi] and Mr. Arima [Sumihisa] and all others—Ms. Samukawa [Akiko] as well.

Ay-O: I loved it.

Yarita: That massive space with an open ceiling, unlike a usual concert hall or auditorium, felt like a hill. There were many stepladders, which were also like hills.

Ay-O: The performers were all young, with an ambition similar to ours—they were so keen and responsive. In the end, someone jumped. We were like, “no, don’t, it won’t be good at all, you’ll hurt yourself!”—but he did!

Yarita: A young man jumped.

Kakinuma: Off a stepladder?

Ay-O: He landed onto that ball. It was four to five meters high, wasn’t it?

Yarita: The magician was also great, and there was the scent from pulled flowers. It was not at all like Mr. Takemitsu’s usual music I had expected to hear; it was a kind of composite art.

Kakinuma: It sounds like performance art.

Ay-O: That’s what Mr. Takemitsu wanted to do. Back then… what was that called… there was music like that, you know?

Yarita: It’s pretty avant-garde, contemporary music.

Ay-O: I forgot the name, but Stock started it. They wanted to bring it to Japan and perform it employing all different elements.

Yarita: There’s sound, visuals, and sensations…

Kakinuma: Mr. Takemitsu was influenced by that piece of Stockhausen? Was he not?

Ay-O: By its concept; that was the motivator. Everyone was so eager to experiment with a new concept—that’s why he did it.

Kakinuma: Not that he was directly influenced, but he had his own ideas and visions.

Ay-O: We all want to try out interesting things, don’t we—not because someone has influenced you.

Yarita: When we live in similar eras in history, similar ideas can be conceived by others as well.

Ay-O: And you can’t help trying out these ideas of others’ as well.

Yarita: Speaking of Nam June Paik, when did you get to know him?

Ay-O: When I was in New York, those related to Fluxus who spoke Japanese all came to me. Paik was the first one among them [from Germany]. All kinds of Japanese people came by when Paik was doing different things, and naturally, he was part of the group.

Yarita: As you were the first Japanese artist to have moved to New York, Ms. Shiomi, Ms. Saito [Takako], and Ms. Kubota [Shigeko] all developed their connections through you.

Ay-O: It was like that. Many Japanese emerging artists moved there at that time.

Yarita: Have you ever been a part of Paik’s cello performance like this one?

Ay-O: With Charlotte [Moorman].

Kakinuma: Were you in the nude performance as the cello?

Ay-O: I wasn’t the naked one, but her. [laughs]

Kakinuma: She was nude and you were the cello in that?

Ay-O: Yeah, like this.

Yarita: She held the string like that.

Ay-O: Charlotte would play me like this, in-between her breasts. [laughs]

Yarita: Sounds nice. [laughs]

Kakinuma: That’s amazing. There’s no caption on the photo, not even your name as the cello.

Ay-O: Because it was Paik’s work—he asked Charlotte to perform it. But when it got popular and he was too busy, he’d come to me, “Ay-o, Help! Help! Help!” “Can you do this?”

Kakinuma: I get it—it’s wonderful.

Yarita: It really is. You and Mr. Paik were friends for a long time, weren’t you. I heard that he wrote a reference letter for your daughter Hanako, too?

Ay-O: Um-hum, for entering an art school. She told me that the students and teachers all came to check her out.

Kakinuma: Which school was it—in the States?

Ay-O: It was—a music school somewhere downtown, on 12th or 13th street.

Yarita: Of course, if someone came in with a reference from Nam June Paik, who was your artist idol—you’d say, “Can you introduce me to him?!”

Kakinuma: When Ben Patterson turned 70, he came [to Japan] and climbed Mt. Fuji although he did not make it to the top. You organized a sightseeing bus tour on that occasion—Fluxus did it back in ’66.

Ay-O: I chartered a bus and waited for him to climb back down to the fifth stage; then we did the Fluxus performance.

Kakinuma: You made the passengers suddenly get off in Aokigahara.

Ay-O: We did different performances of Fluxus during the ride.

Yarita: I know you got off the bus a few times. In Aokigahara, you performed Rainbow Music, like this.

Ay-O: I do stuff like that all the time—it’s boring to just stay on the bus, no?

Yarita: But your tour comes with many different events.

Kakinuma: You originally put together this tour with Mr. Akiyama [Kuniharu] back in ’66. How did the idea of the sightseeing bus come initially?

Ay-O: We had different ideas but decided this would be the best. For one, we wanted to charge the audience a fare for the ride—that was the main thing, among others.

Kakinuma: I think it’s a unique approach to use transportation.

Ay-O: Isn’t it? We wanted something unusual and fun on the bus. We also went to Sengakuji on that occasion. Sengakuji was great.

Kakinuma: Did you do similar performances in the States as well, using different modes of transportation?

Ay-O: Yes, we did it there too.

Kakinuma: What kinds of transport? I have read somewhere that you used a gondola, a rainbow gondola or something like that in Venice. You frequently organized that kind of event using vehicles, I suppose?

Ay-O: We did, it was something entertaining.

Yarita: Bus tours are great.

Ay-O: Charlotte couldn’t swim but she went into the water. She must have swallowed so much. She just jumped in even though she couldn’t swim! How crazy it was.

Kakinuma: I’ve also heard a story that Mr. Maciunas proposed you all buy a building and live together so you became co-owners and turned it into communal housing?

Ay-O: He came up with the idea and we first bought our loft building in New York together. He arranged these deals so he got a space, an apartment, say, on the first floor. That was his share for organizing it. There were three to four properties spread around the city.

Kakinuma: You thought of forming a commune?

Ay-O: Meanwhile, George found a… it was for horse racing … the American kind, where they pull a cart, like…

Yarita: A trailer?

Ay-O: Like a trailer, but it’s for horse racing.

Yarita: Must be the horses that pull a cart or carriage.

Ay-O: It was extremely beautiful. George bought a property from the owner. He always made money selling things but he ran out of business ideas so he bought it.

Kakinuma: And then, you bought the building together.

Ay-O: George wanted to sell the units to everyone to make a profit because he himself needed money.

Kakinuma: Did you also buy it?

Ay-O: No I didn’t. When I went to take a look, it was like this small house built between rivers. I had said I’d buy it but didn’t in the end. No one bought it after all.

Yarita: Oh, no! [laughs]

Ay-O: I told George that it’d be best to call up Yoko [Ono] and ask her to buy—Yoko had money, you know. So he contacted her although he had no idea what it was all about. He was rather naïve so he didn’t even know how big The Beatles were. Anyway, John and Yoko came by and George tried to sell them one of his properties but they didn’t buy it after all.

Kakinuma: George Maciunas was trying to make money through things like that.

Ay-O: He told me later, “Ay-O, it was incredible; so many journalists showed up!”

Kakinuma: There’s no doubt if Yoko and John Lennon came.

Ay-O: He was a funny guy, you know.

Yarita: He must have not realized the significance of them coming.

Kakinuma: That’s something, isn’t it, that he didn’t know The Beatles. [laughs] Coincidentally, John Cage also purchased a communal house in Stony Point around that time.

Ay-O: He had been living there a long time.

Kakinuma: Have you been there?

Ay-O: I have, maybe once, to visit friends. Those guys were doing all kinds of stuff, like mushroom picking.

Kakinuma: Did you participate in that?

Ay-O: Um-hum.

Kakinuma: That sounds like fun.

Yarita: I wish I witnessed that or took part.

Ay-O: We’d swim in a pond, men and women separately—we all swam naked and took photos. I can’t find them now though.

Kakinuma: Is it also true that you planned to buy an island and move there?

Ay-O: We didn’t buy it in the end, but went there to take a look.

Kakinuma: You yourself didn’t go, did you?

Ay-O: No I didn’t. Yoshi [Yoshimasa Wada] went though. He stayed over night there; it’s a deserted island so I don’t know where he slept but he did. He was peeing in the bush and got into some poison ivy. It got swollen so he went to the beach the next day…

Kakinuma: To cool it down. [laughs]

Ay-O: It was Yoshi and… who was it, I forget…

Kakinuma: That deserted island was a Caribbean island, right? Yoshi Wada and maybe Joe Jones?

Ay-O: No, not him, someone else who returned there from New York and became a school teacher. It was a well-known school.

Kakinuma: Not Ken Friedman?

Ay-O: No. I wonder if they still have them—I was told that the school had two limos and chauffeurs.

Kakinuma: Another thing was, while you were determined to go against abstract painting and adhere to the “concrete”, you were also interested in musique concrète, even before going to New York. You said that Mr. Mayuzumi [Toshirō] played a musical saw for you—do you remember meeting Mr. Mayuzumi in Yoko Ono’s loft? And the saw to play music with?

Ay-O: I know, I know.

Kakinuma: And he played it for you; did he?

Ay-O: That’s right.

Kakinuma: You went to listen to him play because you were interested in musique concrète, right?

Ay-O: It was rather popular to play music using unconventional instruments.

Kakinuma: You had said you were interested in that even before moving to New York?

Ay-O: Um-hum.

Yarita: So you always liked things that weren’t mainstream.

Kakinuma: And you had many different interests.

Ay-O: I suppose. I was interested in the latest music—art as well. I’m attracted to the latest anything.

Yarita: You look for things that no one has done, or else it’s not new.

Ay-O: I like things on the cutting edge.

Yarita: I guess you do, but in your case, you discover new things through concepts rather than intuition, right?

Ay-O: To find out what this new thing is, you must try it out yourself though. Doing is the best.

Kakinuma: Another endeavor was to serve various dishes as artwork to be eaten. You fried up things, like a bank note?

Ay-O: Tempura?

Kakinuma: Yes, tempura. Did you eat it?

Ay-O: You mean sweet potatoes? [**The Japanese term for a bill sounds the same as a sweet potato]

Yarita: No, I mean cash. [laughs]

Ay-O: Oh, that one—I did it a couple of times in Germany and in Europe. The bill was the equivalent of 5,000 yen or so—I let someone who had the bill fry it up and make it into a tempura, then he’d eat it.

Kakinuma: Did he? [laughs]

Ay-O: I didn’t, though.

Kakinuma: What was it about?

Ay-O: Don’t you think it’s funny to eat money?

Kakinuma: Some people say Fluxus is a joke, not art.

Ay-O: That’s alright.

Kakinuma: Are you OK about that?

Ay-O: I have no problem with it.

Yarita: I think it implies that humor is also an aspect of Fluxus. You don’t aim at making people laugh, but often, something new, peculiar, or strange provokes all kinds of emotions in the audience—sometimes fear or surprise, and other times laughter and smiles. What Fluxus was doing was not meant to be funny at first, but in the process they generated many humorous moments.

Kakinuma: Isn’t that interesting. There’s lots of humor in Fluxus for sure.

Ay-O: We had a weeklong gathering “on humor.”

Kakinuma: A seminar.

Ay-O: It was in Shiga Kogen, with five to six people, or maybe it was seven to eight.

Yarita: Sukeda Kenryō showed me the documentation.

Ay-O: Right, Sukeda was among us.

Yarita: If you’d like to know more about it, we could visit Mr. Sukeda.

Kakinuma: Sure. I’d also like to ask you about this Fluxus’ image with its tongue stuck out—it looks like an image from ancient Mexico or somewhere.

Ay-O: It is.

Kakinuma: What is this one, the hand?

Ay-O: That, George found it somewhere. It’s printed this big and we’d stick them all over.

Kakinuma: Also, this image of a young Chinese monk exposing his bottom—where did it come from?

Ay-O: Where would it have been… I don’t know.

Kakinuma: This one and this, and this hand are like the symbols of Fluxus?

Ay-O: One day, Shigeko made an image [with her crotch].

Yarita: Vagina Painting?

Ay-O: Yeah, Vagina Painting. I think that’s what it was—probably an illustration for that?

Kakinuma: Is it, really!?

Ay-O: Shigeko didn’t do much but she made that one. She complained later, “My crotch, my crotch hurts…”—it would, wouldn’t it? [laughs]

Kakinuma: It certainly would. I heard that Mr. Paik told her to do that.

Ay-O: I can see it.

Kakinuma: Wow, this is Shigeko…

Yarita: Somewhat oriental… it shows a bit of orientalism.

Ay-O: You actually found this? You’re thorough…

Yarita: This image often appears in publications.

Kakinuma: Yes, it always comes up in association with Fluxus. Also, George Maciunas made designs for everyone’s name? This one is for Ms. Shiomi; yours is beautiful, too. What was his intention behind designing everyone’s name?

Ay-O: Well, George was a designer and loved doing things like that.

Kakinuma: You mean he designed it for everyone in the group? All of them look fabulous.

Yarita: These names alone are art, aren’t they? I think “Ay-O” by itself is art.

Kakinuma: Do you have any thoughts on Fluxus at this point? If there’s anything you would like to say—what do you think Fluxus was?

Ay-O: [laughs] I wonder what it was… A strange group, I suppose; it was an odd bunch.

Kakinuma: You were all over the world, but connected with a strong sense of camaraderie—a fantastic group, I find.

Ay-O: Perhaps so, but it was a funny relationship we had.

Yarita: You mentioned Paik asking you for help; you all helped each other, right?

Ay-O: Maybe.

Yarita: Milan Knizak said…

Ay-O: Oh, that was Milan, by the way. [Milan went to the Caribbean island with Yoshi Wada.]

Yarita: Oh it was? When Milan Knizak was not able to get back into his country, he contacted you.

Ay-O: Yeah, like, “Help me!” [laughs]

Yarita: He sent telegraphs to all the countries.

Ay-O: He did, all over the world. Someone in Fluxus copied it recently, the one who drives a cab—what’s his name, do you know? Not a famous one—he makes a living driving a taxi in New York.

Kakinuma: Even still?

Ay-O: I suppose so, if there’s no other income. He came to Tokyo for the occasion of my exhibition and asked me for an interview. We spent two days on that.

Yarita: You did the interview in Kiyosumi Park?

Ay-O: Yes, we had it there; beneath the park.

Kakinuma: I find it wonderful that you are all good friends and help each other. For instance, you support one another by staging each other’s performances rather than each artist performing his or her own work.

Ay-O: Well, to become a friend of an artist, you must value his or her work first; otherwise, you are no friend.

Kakinuma: Is that so? [laughs]

Ay-O: I think it was the truth.

Kakinuma: Once you valued each other’s work, you became close.

Ay-O: And consequently, if someone just said “let’s do that performance,” everyone would come along—we never discussed it.

[An earthquake occurs]

Kakinuma: Ah, an earthquake!

Ay-O: It is—we can duck into here if it gets big.

Yarita: We’re fine—it’s not that bad. Shindo [intensity] three or four? The epicenter has been off the coast of Chiba lately.

Kakinuma: There must be many earthquakes around here, I suppose?

Ay-O: Yes, there are quite a few.

Yarita: The ground here is… it must have been the beach here?

Ay-O: Probably—the ocean’s just over there.

Kakinuma: All right, now, Ms. Yarita, do you have anything else you would like to ask?

Yarita: I’ve heard stories about the many friends you have, but what was he like—what’s his name… the one who does a headstand on your birthdays?

Ay-O: He does a headstand on my birthday and sends me the photo—his brother managed Yoko, didn’t he? [He meant Geoffrey Hendricks.]

Yarita: Jon Anderson is Yoko’s manager, I believe.

Kakinuma: Is it not Brecht?

Yarita: Not George Brecht.

Kakinuma: There’s an artist list here but I don’t know which one.

Yarita: I’m sorry I don’t know either.

As long as you have a concept, you can make Fluxus-like art without spending money. For instance, Milan Knizak’s using things found on the street—we have made so many necklaces—and the headstands as well. This idea that a unique concept becomes art with little money somewhat resonates with Pop Art—Al Hansen, for example, had similar approaches. He’d make work like these, gluing together cigarette butts or Hershey’s wrappers. They also show a refreshing concept of art that won’t cost you much to make. Many artists have made artwork like these, highlighting their ideas.

Ay-O: Their art show clear concepts—I think that’s what it is.

Yarita: Then everyone gets inspired to conceive his or her own.

Ay-O: Um-hum.

Yarita: Mr. Hansen’s choice of materials too, is stimulating. Usually a painter needs a canvas, an easel, and oil paints. But the painters in the 19th century, in Montmartre in Paris for example, struggled to afford paints. On the other hand, the artists in the 20th century would make necklaces with found objects or works with cigarette butts, without spending much money —that’s what I love, as a reflection of the 20th century.

Kakinuma: I agree.

Yarita: What is important is the concept, and that’s what you mean by “to do ideas”, I guess?

Ay-O: One thing is, I am interested in art that doesn’t cost money. Even if you apply so many thick layers of paint, it’s just paint.

Yarita: It is still a mere object.

Ay-O: Precisely. You can’t ask for money, you know.

Kakinuma: The fact that you got those sponges for free might have been an important aspect to that work.

Yarita: With a simple idea, common materials found in the 20th century’s mass-consumer society were turned into art; or you awoke everyone’s senses through your Finger Boxes—Fluxus members contributed to these new forms of art in the 20th century.

Kakinuma: Could we say then that this began with Marcel Duchamp ultimately—using readymade or already existing things to make art while focusing on a concept?

Ay-O: I don’t mean to discredit Duchamp, but we all had ideas and he was not the only one. I know everyone loves Duchamp—so do I. I went to New York because Duchamp was there.

Kakinuma: You met him at a gallery, didn’t you?

Ay-O: Many times.

Kakinuma: What was he like?

Ay-O: An old man. [laughs] He was quite old.

Kakinuma: He must have been by then.

Ay-O: He was an extremely intellectual old man.

Kakinuma: There are so many questions I should be asking as you have had many experiences and met many people—you must have a lot of invigorating stories to tell. Could I ask you one more thing—what did you think was the difference between “happenings” and “events”? Kaprow’s works were “happenings” whereas Fluxus members called their activities “events.”

Ay-O: A “happening” was for one time whereas “events” could be done many times. [The battery of the video runs out] That was our view, basically.

Kakinuma: Some say Kaprow is…

Ay-O: No, Kaprow is the Happening.

Kakinuma: Exactly, they say he is not Fluxus.

Ay-O: No, he isn’t.

Kakinuma: He is not, I guess?

Ay-O: He preceded Fluxus.

Kakinuma: He had some connections with Fluxus but was never a member.

Ay-O: George Maciunas coined the name “Fluxus” but Kaprow was before that, you know.

Yarita: Yes, as Maciunas gave the group its name…

Kakinuma: I see, so that’s the difference. You met Cage a few times, I believe?

Ay-O: Yeah, I did.

Kakinuma: Do you remember anything about him that left an impression on you?

Ay-O: I do, but what can I tell you?

Kakinuma: Well, I suppose [laughs]. That’s OK. Anything else?

Yarita: I’m OK.

Kakinuma: Thank you very much for this opportunity. It’s been fascinating.

Yarita: Thank you so much.

Kakinuma: I’m really hoping that you will organize another event like the one you did at MOT—“Viva! Fluxus.”

Ay-O: Viva! Fluxus.

Kakinuma: It was the last event everyone participated in.

Yarita: I really enjoyed it.

An illustration drawn by Ay-O for 07th