靉嘔 オーラル・ヒストリー

- JP

- EN

靉嘔 オーラル・ヒストリー

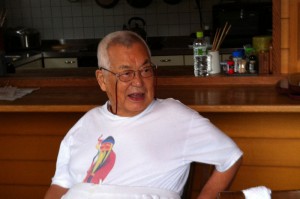

2014年6月28日 靉嘔アトリエにて

インタビュアー:ヤリタミサコ、柿沼敏江

書き起こし:永田典子

靉嘔 (あいおう 1931年~)

美術家

1950年代にデモクラート美術家協会に参加した後、1958年に渡米。触覚による《フィンガー・ボックス》、「エンヴァイラメント」と呼ばれるインスタレーション、光のスペクトルの色で塗り分ける「虹」の作品で注目を集める。国際的な前衛芸術運動であるフルクサスに参加して、数々のイヴェントを手掛ける。靉嘔氏と交流がある美術批評家の本阿弥清氏と、2012年に東京都現代美術館で開かれた「靉嘔 ふたたび虹のかなたに」展を担当した西川美穂子氏をインタビュアーに迎えて、茨城県行方市での生い立ち、東京教育大学(現筑波大学)の学生時代。デモクラート美術家協会での活動、渡米後の作品やその展開、フルクサのメンバーをはじめとするアーティストたちとの交流、帰国後の活動などについてお話しいただいた。

柿沼:今日は2014年6月28日。靉嘔さんのアトリエでインタヴューさせていただきます。インタヴュアーは、詩人のヤリタミサコさんと、わたくし柿沼敏江でやらせていただきます。よろしくお願いします。

靉嘔:6月28日ですかぁ。土曜日ですね。

柿沼:はい。このあいだ東京都現代美術館で「フルクサス・イン・ジャパン2014」を拝見させていただいたのですけれども、靉嘔さんも参加されていて。その時に出演されて、ほかのメンバーともお会いになられて、どのようにお感じになりましたでしょうか。

靉嘔:誰と会って?

柿沼:ベン・パターソン(Ben Patterson)さんとか、エリック・アンダーセン(Eric Andersen)さんとか、昔のフルクサスのお仲間もいらっしゃって、いかがでしたでしょうか。

靉嘔:いやあ……(笑)。いやあ、ぐらいなもんですよ。はい(笑)。

柿沼:あの時にパフォーマンスの作品を3つ拝見させていただきました。1つが《モーニング・グローリー Morning Glory》(1976年) という歯磨きの作品で、もう一つが《はひふへほ》(1966年)という笑う作品で、もう一つが《07th》。オー・セヴンスでよろしいんでしょうか。

靉嘔:ゼロ・セヴンスですな。

柿沼:この3つを拝見させていただきましたが、これは靉嘔さんの美術のほうの作品評にはあまり出ていなくて、パフォーマンス作品としてやられているものなのですけれども、これらについて。

まず《モーニング・グローリー》、これはいつ頃最初にされた作品か覚えていらっしゃいますでしょうか。

靉嘔:いません! 覚えてません(笑)!

ヤリタ:だいぶ前、フルクサスのニューヨークのときのものにもたまに出てきませんかね。

靉嘔:《モーニング・グローリー》というのは朝顔ですからね。「朝顔に つるべ取られて もらい水」(注:加賀千代女の俳句。後年に「朝顔や」に直された)なんですよ。ということなんです。

柿沼:歯磨きというのは、(カールハインツ・)シュトックハウゼン(Karlheinz Stockhausen)の《オリジナーレ》という曲でもされていますが、それとは別。

靉嘔:同じといえば同じですけど、別といえば別ですよね(笑)。

柿沼:そこから始まった作品と考えてよろしいでしょうか。

靉嘔:いやー、分かんないですね。

柿沼:では《はひふへほ》というのは、どうでしょうか。笑う作品ですけれども。インターネットで拝見したら、昔、刀根(康尚)さんと一緒にされている映像が出ているのですけれども。3人で笑われている作品で、たぶんニューヨークでやられているんだと思いますけど。

靉嘔:あれはね、エメット・ウィリアムス(Emmett Williams)っていう僕の友人がいて、二人ともユーモアについて興味があるんですよね、非常に。ユーモアについて興味があって。それだけですね。

柿沼:最初はいつだったかは覚えていらっしゃらないですか。

靉嘔:いや、もう……。ユーモアっていうのはね、「はひふへほ」なんですよね。それを全部いろいろ、所によって、時によって、分解してみたり、テストしてみたりするというのが僕のそれなんですけどね。そういうことです。それは作品があるんですね。キャンヴァスのでっかい作品があるんですよ。

柿沼:《はひふへほ》の! それは虹色で描いてあるんですか。

靉嘔:字が書いてあります、はひふへほって。

柿沼:黒い字で?

靉嘔:いや。展覧会に出てましたよ、僕の展覧会に。

柿沼:そうですか。

靉嘔:出てたよね?

飯島郁子:カタログに出てる。

ヤリタ:2012年の東京都の現代美術館のほうに出てますね。

靉嘔:ずいぶん古いカタログですね(笑)。

柿沼:これは2004年です。浦和の時のです。

ヤリタ:現代美術館のほうに出ていると思います。

柿沼:それはビジュアルな作品としてあって、パフォーマンス版の《はひふへほ》というのがあるということで。

靉嘔:そうじゃなくてね。「ユーモアについて」という……何て言うのかな……あれは何と言ったっけ、ユーモアについて軽井沢でやったのは。

飯島郁子:セミナー「ユーモアについて」。

靉嘔:「ユーモアについて」というセミナー(注:1976年 8月 23日~28日まで、志賀高原ホテル)をやったんです。それをやったのは、僕とエメット・ウィリアムスという二人が講師で、5、6人集まって。あれはどこでしたっけ。

飯島郁子:志賀高原じゃなかった?

靉嘔:志賀高原ね。ハイツ。あれは宿屋というんですかね、ああいうのは何と言うのかな。

柿沼:ホテルではなくて。

飯島郁子:ヒュッテというのかな。

靉嘔:ホテルはホテルですけど、そこでみんなで合宿して。僕とエメットが講師になっていろいろやったんですよ。

柿沼:ああ、その時にもうあれをされているんですか、《はひふへほ》。

靉嘔:その前に、いつも僕はユーモアについて、ユーモアって何だろうということをいつも考えていたわけですね。それをいろいろやって、はっきりさせるために。日本語では「はひふへほ」がユーモアなんですよね。ははは、ひひひ、ふふふね。

ヤリタ:音として、息がものすごく出る音ですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。それで「は」のときには歯を磨いたんですね(笑)。「は」のときに歯を磨いたということは、「朝顔に つるべとられて もらい水」というのあるでしょ、日本の古典に。それに引っかけたんですね。そんな難しいことじゃないんですよ。ただ引っかけたんです。それで「モーニング・グローリー」というタイトルで。それが出たら、ほかのいろんなことをまたくっつけて、「はひふへほ」のいろんなことをくっつけていろんなことをやったんですね。

柿沼:ほかに、例えば「ひ」というのはあるんですか。「は」が歯磨きだとすると、「ひ」は何かあるんですか。

靉嘔:「ひ」? あるんですよ。全部あるんです。

柿沼:「はひふへほ」全部ある。じゃあ「ひ」は何ですか。

靉嘔:忘れちゃったですね(笑)。あるんですよ。

柿沼:全部あるんですね。なるほど。そうするとこのあいだ両方やったのは意味があることだったわけですね。

靉嘔:そうですねえ。

柿沼:じゃあもう一つの《07th》。このタイトルはどういう意味ですか。

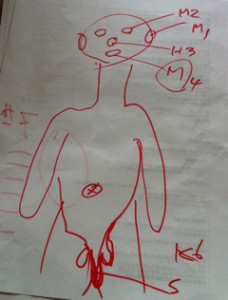

靉嘔:僕は穴が、《フィンガー・ボックス》(1963年頃)でも何でも、穴が僕のなんか特許みたいなもんなんです、穴がね(笑)。だから穴についての考察がいろいろあるわけですけれども。7thの。

柿沼:ゼロは穴ですか。

靉嘔:これ7つあるわけですよ、7th。

柿沼:穴の中からいろんなものが出てくる。

靉嘔:そういうことじゃないです。それは後からくっついてきたもんで。穴についての考察ですね。

柿沼: 7thはどういう意味ですか。7つあるということですか。

靉嘔:これがね、耳、1ですね。

ヤリタ:人間の体ですね。

靉嘔:これ、目ですね。これは鼻ですね。

柿沼:nose。

靉嘔:こんなことやってたんじゃ来年になっちゃいますね(笑)。

柿沼:すいません、簡単で結構ですので。

靉嘔:簡単じゃあ。とにかくこれは60年間ぐらいの間にやったことですから、そう簡単にはいかないんですよね(笑)。

柿沼:いかないんですね。すいません。

ヤリタ:長い考察が。

靉嘔:これ鼻ですね。口。1、2、3、4。これはおしっこするとこね。尿道の穴ですね。あと肛門があるでしょ。これが6ですか。肛門が6。それであともう一つ、産道かな。何て言うんですか。

柿沼:産道。女性の場合です。

靉嘔:ありますね。全部で7つですね。「07th」というのはそういう意味です。

ヤリタ:すごい! 人間の開口部、世界と通じている穴。

靉嘔:何かの時に一日中とか10日とか、穴のことばっかり考えているときはいろいろ出るんですね。で、「07th」なんです。

柿沼:そこで銅像を見ましたけど、先生の、口を開けて。あれも穴から入って。

靉嘔:あれは、飲むとここから出るんですよ、ほんとに、本物。でも子供が、ガキどもが石を入れちゃって、詰まっちゃって(笑)。

ヤリタ:便秘になっちゃったんですね(笑)。残念ですね。ブロンズの小さいのはありますよね。

靉嘔:あれはお米を入れると出るんですね。

ヤリタ:お米を観客が入れて、ツルンってお尻から。

靉嘔:これはね、女の人なんですよ、07thは。男は06thなんですよ。だから足りないんです。

ヤリタ:やっぱりあの穴からいろんなものが出てくるって、そういうイメージじゃないんですか。生まれ出てくる。赤ちゃんが生まれ出てくる感じ。

柿沼:あれはニューヨークでされたものですか、最初、《07th》は。

靉嘔:そうですね。だって僕ずっとニューヨークですから、作ってるのは。やってるのもニューヨークなんですけども。

柿沼:毎回出てくるものは違うものが出てくるんですか。

靉嘔:そうです。そうでしょうね。いつも違うものを食べるわけだから(笑)。

柿沼:あの時インスタントコーヒーを階段にまかれていましたけれども、あれは穴から出てくるのではなくて、それとは別に。プーンとにおってきたんですけど、コーヒーが。

靉嘔:あれはね、会場にまかなきゃいけないんですよね、ほんとはね。ところがみんな遠慮するんですよ。汚すとかね。昔、僕はまいたもんですよ。どんなきれいなとこでもまくんですよ。

ヤリタ:だって五感を刺激しなかったら。芸術は見るだけじゃなくて、聴いたり感覚的に。

靉嘔:水まいたりね、ジョウゴで水まいたり。

柿沼:色彩的にも、シェーヴィングクリームが出たり、ケチャップが出たりいろんな色が出てきました。

ヤリタ:色はすごいですね。風船もいろんな色が出てきて、カラフルで。

柿沼:楽しかったです。

ヤリタ:何が出てくるんだろうという、ドキドキ。

柿沼:期待感で。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんのおイタズラが、どのくらい大きなイタズラが出てくるんだろうっていうドキドキ感はすごくありますね。楽しかったですね。

柿沼:見ていると、ちょっと子供の頃に帰るような気持ちになりますね。

靉嘔:そうですよ。何にも違いありません。同じですね。

柿沼:イタズラでやっているような感じになります。

靉嘔:子供の心が一番いいんですね、それは。なれればね。人間が子供の心に帰れれば一番いいんですよね。一番本当のものを持ってくることができるわけですよ。

ヤリタ:新鮮な気持ちで、空が晴れた曇ったといって、それで楽しい気持ちになりますよね。

靉嘔:生まれてはじめてのもの。あと、おそがあるんだね、これね。

柿沼:おへそは、穴は開いてないですけど。

靉嘔:前は開いてたわけでしょ。

ヤリタ:お母さんのお腹の中にいるときは産道とつながってるから。だから産道だけというよりは、男性でもやっぱり産道とつながっているという意味では。へそ・産道というのがカップリングした感じで7番目じゃないんですかね。

柿沼:なるほど。じゃあ男性でもいいわけですね。

靉嘔:そうですね。アートとかそういうものは、そういうひどいもんですよ(笑)。

柿沼:ちょっと昔に戻らせていただいて、ニューヨークに行かれた頃からのことを少しお伺いしたいと思うのですけれど。ヤリタさんいかがでしょうか。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんのお話を聞いているときに私がすごく印象に残ったのは、ニューヨークに最初に行ったとき、ギャラリーにみんな断られたって。自分の作品を持ち込んで。全部回られたとおっしゃっていましたね。

靉嘔:そうですね。ニューヨークは140~150軒あるんです、画廊が。1軒も引っかからなかった(笑)。それを3回やったんですよ、僕は。

ヤリタ:3回。150軒を3回だと450軒回ったということですね。

靉嘔:そのたんびに、あるときはでっかい作品を。この部屋ぐらいでっかいのを巻いて持って行ったりね。

ヤリタ:誰もみんな「No」と言うんですか。

靉嘔:「No」ですね。

ヤリタ:でも靉嘔さんとしては、日本である程度やってきたし、自分の自信作と思って持って行ってますよね。

靉嘔:そうですよ。僕は勉強しに行ったんじゃないんですよ。アメリカに絵を勉強しに行ったんじゃないんです。何か新しいものを、僕のものを持って行って売りつけようと思って行ったわけですよね。

柿沼:そしたら。

靉嘔:誰も買ってくれない(笑)。

ヤリタ:普通ならその段階で、志の弱い人はシュンとなっちゃって帰ってきそうなものなんですけど、靉嘔さんはそこからもうひとつ自分で。

靉嘔:いつもクシュンですよ、それは(笑)。ひどいもんでしたよ。

ヤリタ:自分の絵にバッテンみたいなのを描いた時期がありますよね。

靉嘔:150軒の画廊を回るでしょ。そうすると「うちの画廊の絵描きはこういう絵描きだ」って見せるんですよね。アクションペインティングのアブストラクト、その頃は。あとは何もないんですから。

ヤリタ:ジャクソン・ポロック(Jackson Pollock)なんかが流行っていた頃ですか。

靉嘔:そうですね。ジャクソン・ポロックじゃなかったら絵描きじゃなかったですよね。

ヤリタ:いやあ、大流行なんですね。

靉嘔:いやいや、いつでも、どこでもそうですよ。今だってそうですよ、何か流行りがあって。まあそういうもんですね。

ヤリタ:そうすると靉嘔さんもアクションペインティングみたいのもしたんですか。

靉嘔:そうですね。だって見向きもしてくれないでしょ。「うちの絵描きはこういう絵描きなんだよ」って僕に言うんですよ、さも「やれ」っていうように。それで2年ぐらいゴチョゴチョしてましたけども。

ヤリタ:アクションペインティングみたいのも作ったけど……。

靉嘔:いやあ、やっぱり僕は降参したんです。アクションペインティングを始めたんです。このぐらいの広さのアパートで、買ってきたキャンヴァスを地面に打ち付けて絵の具を流すんです。

ヤリタ:ニューヨーク派のやり方で。

靉嘔:アブストラクターとして絵を描いたんです。バケツに絵の具を溶いてまくんですからね、居られたもんじゃないですよね。で、逃げ出して。それでタイムスクエアへ行って映画を3本ぐらい観るんです、安い映画を。2本立てを3本だから6本だね。

柿沼:それで何か考えが変わるんですか。

靉嘔:いや(笑)。

柿沼:そうじゃなくて?

ヤリタ:絵の具が乾く間。テレピン油のにおいとかってすごい。

柿沼:ああ、そういう意味なんですね。

靉嘔:臭くてね。死んじゃうんですよ。

ヤリタ:酸欠になるし。揮発性の中毒っぽくなるんじゃないですか。それを避けるために時間つぶしに。

柿沼:待ってるわけですね。

靉嘔:テレピン油ですからね。ガソリンですよね。

ヤリタ:映画6本観て、帰ってきて自分の作品を見てみたら。

靉嘔:僕は絶対にね、日本を出るときに、「人の真似をしない」って誓って行ったんですよね。結局、真似をしたじゃないですか。で、居ても立ってもいられないわけですよ、自分にウソをついてるわけで。それで喧嘩するんですよね。当たると幸い、誰でも喧嘩するんです。喧嘩してるうちに、「あ、俺、英語しゃべれるんだ」と思ってね(笑)。

ヤリタ:英語の練習になりましたね、喧嘩も。

柿沼:喧嘩できると一人前って。

靉嘔:喧嘩するのが一番いいですよ、言葉を覚えるにはね。言いたいことだけ言えばいいわけですから。

柿沼:それでその後どうなりましたか。

靉嘔:それで自分に嫌になっちゃってね。今まで描いたニューヨーク・スクールのアクションペインティングに全部にバツをつけたんですよ。書いてありますよね、ここに。バツをつけて。

ヤリタ:捨てられたものもあるとお聞きしてますけど。今でも回顧展だとバツがついた作品がいくつも出てますけど。靉嘔さんのお話だと、バツもきれいに描きたくなったとおっしゃってましたね。

靉嘔:やっぱり絵描きなんですよね。バツをつけると、「ああ、つけ方がよくないな」って。キャンヴァスを切ってもね。そういういろいろありまして。全部バツをつけて。もうどうしようもないよね。部屋中バツ、でっかい。キャンヴァスなんていうのは、半分壊れたようなとこへ行って、そういうものを剥がしてくるんですよね。剥がしてきて、それに白を塗ってキャンヴァスにするんです。

ヤリタ:中古ですよね。リサイクルといえば聞こえはいいけど。

靉嘔:そのぐらいの絵を1ヶ月に4、5枚描くわけです。20~30枚たまりますよね。たまって最後はいろいろやって、バツじゃすまなくなって燃してみたり、焼いてみたりね。

ヤリタ:人と同じことをしない、人の真似をしないということが靉嘔さんの一番の。

靉嘔:いやあ、人の真似、絵描きでもなんでもみんな人の真似なんですよね、だいたいが。音楽でも何でも人の真似なんですよ。そういう真似をしまいと思ったら、どうして真似をしない方法があるかということを考えなきゃ。大変ですよね。

ヤリタ:ゴッホやセザンヌにはなるまいと思ったら、自分のモチーフというかやり方みたいなものを何かから探さなきゃいけないですね。

靉嘔:それで今までのキャンヴァスを全部切り裂いてね。この作品どうしたらいいかなと思って考えて。そういうものを並べてみたら、部屋になって。変わった、ボロボロの家ができて。それを作品にしたんですよ。

柿沼:それが《ティーハウス》(1961年頃)ですか。

ヤリタ:そういう布の小さな小部屋みたいなのがありますね。

柿沼:それも穴が開いてるんですね。これには載ってないか。靉嘔さん個展のだったら載っているんですけど、これはフルクサスなので、《ティーハウス》は載ってないかもしれないですね。

《ティーハウス》を作ったわけですね。

靉嘔:そういうふうになっちゃったんだね。すると僕のとこにみんな見に来るんです、変な絵描きが。変な友だちですよね、変な友だちが見に来て。まあそういう仕事をしていたわけですね。

ヤリタ:そうすると自然発生的に、ニューヨークの画廊には掛からないような絵描きさん、アーティストたちがだんだん集まってきて、交流ができてきて。

柿沼:その頃オノ・ヨーコさんも見にいらっしゃったんですか、《ティーハウス》を。

靉嘔:そうです。

ヤリタ:ヨーコさんとか、篠原有司男さんとかもそうでしたね。あと河原温さんとか。何人か日本から行っているアーティストさんもいらっしゃったでしょうし、オノ・ヨーコさんあたりからエメット・ウィリアムスとかジョージ・マチューナス(George Maciunas)とかとつながりが出てくるんですかね。

靉嘔:そうですね。変な連中が集まって、変な連中でグループショーをやったり。誰かがパフォーマンスを始めるとみんなパフォーマンス、僕もパフォーマンス。みんなそういうんですね。変なグループなんですよね。でもそういうのは、人の真似をしてるんじゃないんだけども、同時に起こるんですね、地球上に同時に起こるんですね。あれは不思議なもんですね。追い詰められるとやることはみんな同じなんですね。同時に起こって。僕がやったことが、あいつも変なことやってるって。見ると分かるわけですよ。「こういうことでああいうことになったんだ」って。行くと、変なハプニングをすると、よく分かるから手伝えるわけですね。

柿沼:その頃、マチューナスにもお会いになった。

靉嘔:その頃、僕は展覧会をやりたいとまだ方々探してたんですけども、マチューナスというのがいるからと。マチューナスというのは絵描きじゃないんです。画廊を持ってたんですよ。

柿沼:それがAG画廊ですか。

靉嘔:AG Galleryですね。

柿沼:そこに連れて行かれて。

靉嘔:そこに行って写真を見せて、「展覧会やりたいんです」って言ったら、「やれよ」って。2~3ヶ月後に来いと、いろいろ相談しなきゃいけないからって。行ったら画廊がつぶれてないんですよね。ジョージは借金でクビが回らなくなってヨーロッパに逃げちゃったんです。夜逃げをしたんです。

ヤリタ:ドイツに行ったということですね。

柿沼:なぜそんな借金をしたんでしょうか。

靉嘔:彼はコマーシャル・デザイナーで、結構いい金を稼いでたんです。月に1,000ドルか2,000ドル。

柿沼:それなのにどうしてでしょう。

靉嘔:全部僕なんかのために金を使ったんですよ。変なアーティストのために変な展覧会をしてみたりね。

柿沼:それでお金がなくなっちゃったんですか。

靉嘔:にっちもさっちもいかなくて、ヨーロッパに夜逃げしたんですね。夜逃げした一つの理由は、ジョージに聞いたのは、あの赤い本、『アンソロジー(Anthology)』というあの本を売りたくて。あれは僕らの仲間が作ったもんです。僕はいなかったんですけども。一冊も売れないんだよね。

柿沼:今だったら高いよねえ(笑)。

ヤリタ:すごい高い。

靉嘔:それを売ろうと思ってそれを持って行って。行っても人は来てくれないから、変わったことをすれば来るだろうと思って、若い子たちを集めてコンサートを開いて、ということを方々でやったんですね、ドイツとか。

柿沼:ヴィースバーデン (Wiesbaden) で第1回のフルクサス音楽祭というのをやっていると思いますけど。

靉嘔:方々でやったんですよ。

柿沼:はい。それが面白いと思うのは、音楽祭なんですよね。展覧会じゃなくて音楽祭としてやっているところが面白い。

靉嘔:コンサートですね。

柿沼:コンサートだというところが面白いですね。

靉嘔:ミュージシャンが多かったんですね。ミュージシャンが多いから、ミュージックの言葉で話すんだな、やっぱりね、コンサートすると。同じようなもんですよね、展覧会を開くと。でもあまりちゃんとした絵描きはいなかったんだろうね。(クレス・)オルデンバーグ(Claes Oldenburg)なんていうのはいたんですけども、それなんかはハプニングばかりやってて、あっという間に有名になっちゃって。スウェーデンの作家ですけどもね。

柿沼:それで彼がニューヨークへ戻ってきたんですね、その後。ジョージ・マチューナスは。

靉嘔:フルクサスという名前で展覧会とかコンサートをやって、戻ってきて、僕の近くに来たんです。書いてあります、これに。展覧会じゃなくて……。

柿沼:YAMフェスティヴァルですか。

靉嘔: YAMフェスティヴァルの前にニューヨークの僕らの仲間がやってたんですね。それはまた別なんですけども。

柿沼:ハット・ショー(YAM Festival Hat Show)というのをされたというのが出ているんですけど。

靉嘔:展覧会でハット・ショーをしようって、みんな帽子を持って。

柿沼:その時にこういう帽子をかぶったんですか。そうじゃないんですか。

靉嘔:アメリカは、4月の何日かな、普通の人が帽子をかぶって街の中をフラフラ歩く。

柿沼:復活祭のあれですか。イースターじゃないですかね。

靉嘔:イースターかな、その時に帽子を。で、帽子と展覧会をやろうとか、いろいろなことをやったわけです。

ヤリタ:いろいろ発想がユニークですよね。

柿沼:そうですね。帽子をかぶって行進するんですよね、その時に。

靉嘔:展覧会もして、画廊でね。

柿沼:それでマチューナスさんがフルクサスのショップを開きたいとおっしゃった。ギャラリーじゃなくてショップを開きたいと。

靉嘔:彼、逃げて行っちゃって、またニューヨークへ戻ってきたんです。僕のとこに来たんです。僕のとこへ来たのが最後かな、ニューヨークで、それで外国へ行っちゃったのかな。それは分かんないんですけども。僕のとこに来たんです。それで画廊じゃなくてショップを開きたいと。そこで売りたい、われわれの作品を売りたいと。「分かった」って。で、彼は借りたんです、倉庫を。「ロフト」って言うんですけど、倉庫を借りて。

柿沼:それが靉嘔さんのお宅のすぐそばだったんですか。

靉嘔:そうだったんです。僕は住んでたんです。日本ではアトリエと言うけど、ロフトって言いまして。仕事場なんだけども。

ヤリタ:その頃の写真を見ると、いかにも倉庫然とした写真が載ったりしていますね。

柿沼:これがそのショップのあったとこでしょうか、フルクサスの旗が出てるんですけど。

靉嘔:これがフルクサスのとこですね。僕のところは1つおいてここだったんですね。僕はいろいろ機械を。その頃ちょうど50ドルでドリルが買えるとか。日本ではそういうことなかったんです。50ドルでドリルを買うとかノコギリが買えるとか。で、興奮してそれを買って、でっかいアルミを買って穴を開けてみたり。それが作品になったんですけど。キャナル・ストリート(Canal Street)というのは、そういうジャンクを売るところなんですよね。知ってますよね?

柿沼:それでオーケストラのコンサートとかが始まって。

靉嘔:ジョージが来て、「隣が空いてるか聞いてこい」って言ったんだよね。「それを借りたい」って言うんだ。で、ジョージのために部屋を3つに分けて、前をフルクサス・コンサート・ホール、真ん中をフルクサス・ギャラリー、最後の部屋をジョージの寝室、ベッドルームにしてやるって。で、僕がやってやったんです。タダ働きだけども。

ヤリタ:大工仕事ですか。日曜大工みたいにですか。

靉嘔:大工仕事をして僕なんかアルバイトを。いろいろアルバイトはやったんだけど、結局、自分がテクニックを持ってるものでやれば一番儲かるわけですよね。そういうことでいろんな機械を買えるようになったので、機械を買って、その使い方も教わって、そういうところを作ってアルバイトを始めたんです。ジョージが注文を取ってるんです。で、われわれは作って。

柿沼:販売するんですか。

靉嘔:金は、コマーシャル・アーティストだから、いろいろな店のショーをするんですね。宣伝をするためにショーをするんですね。

柿沼:客寄せみたいなことで。

靉嘔:そうそう。そういう仕事を見っけてくるんですよ。どういうふうに飾ってやるかって描いてきて、僕なんかは労働。僕と友だちと二人で労働して、そういうものを作って。ジョージは、そういうものを請け負ってきて僕たちに金を払ってくれるんです。

ヤリタ:じゃあ注文取る人、作る人、演じる人ってうまくフルクサスのみなさんがいろんな役割分担ができるんですね。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんが虹を描き始めたというのはその頃ですか。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:それはどういうふうに思いつかれたんですか。

靉嘔:人の真似をしないと書いたけども、どんな仕事すりゃいいか考えたんですよね。僕も少しは考える(笑)。

ヤリタ:悩んだ、悩み抜いたあげくだから(笑)。

靉嘔:考えたんですけども。人の真似をしないでものを作ろうと思ったらどうしたらいいかったら、僕の感覚を生かしてね。感覚、六感ってありますよね。味覚とか聴覚とか視覚とか、それから嗅覚、それからタッチ、触覚ね。それを一つずつ確かめていこうということを。僕が知ってるかぎりの――僕は大学を出ただけで、どうしようもない、実際の知能があるわけじゃないんだけども――僕が知ってる限りの知識でそういうことを。

家はだめになっちゃったわけですね。

ヤリタ:お父さまが飯島家の跡取りですか。

靉嘔:僕の家は飯島っていうんですけども、親父は次男なんですよね。長男が跡取りだった。親父は兵隊だったんで、帰ってきてうちの手伝いをして。親父は百姓好きだったね。

柿沼:お父さまはパイロットをされていたんですか。

靉嘔:そうです。親父は海軍のパイロットですね。

柿沼:靉嘔さんもここでお生まれになったんですか。

靉嘔:ここで。ここは親父の土地ですから。兄貴と2人兄弟なんですね。伯父さんが死んで、僕は逃げ回ったんだ、「百姓やれ」っていうんで。でもしょうがないね。僕はアメリカへ行っちゃって、いないんですけども。そしたら親父も死んで、伯父さんも死んで、結局僕が跡取りで。昔、日本は、法律ができて、一つの家が持てる面積の田んぼが決められちゃったんですね。それ以上持てないんです。だから親父の分と伯父さんの分、僕は両方もらって(笑)。それに畑があるでしょ。僕は何もしないんで。

ヤリタ:この辺はずっと飯島家の土地なんですか。

靉嘔:田んぼはそうですよ。下にあって、上にもあるんですけどね。3か所あるんです、でっかいのが。畑もわりにたくさんあるんですね。みんな貸してて、僕は知らないんですけどね。

柿沼:ではインタヴューに戻りましょうか。

ヤリタ:虹を見つけて、虹を描き始めたところから。自分の感覚、第六感とかの感覚があって。

靉嘔:そうそう、感覚、六感を追求しなきゃいけないっていうんで追求を始めたんですね。ある日、展覧会をやってくれるところがあって展覧会をやったら、それを見に来た人がいて。僕はちょうどスポンジを使った作品を作ってたんです。そしたら「おまえアーティストか」と言うから、「そうです」ったら、「おまえこういうスポンジいるか?」って言うんですね。「ほしいか」「ほしい」「じゃああげるから」って。2、3日たったら、僕のキャナルストリートの下にでっかいトラックが止まるんです。こんなでかいブラックのやつがね、スポンジをどんどんどんどん運んでくるんだ。僕はtwo flights upで。3階なんですけど、ニューヨークはそうやって勘定するんですね。one flight up、two flights upって。そこまで全部運んで。1人でですよ、全部運んでくれて、部屋中スポンジだらけになっちゃった。お金もないし、あるもので仕事する以外にないですからね。まあ触覚の仕事を、「これはいいや」と思って、それで始めて。それで《フィンガー・ボックス》というのができたんですね。

ヤリタ:《フィンガー・ボックス》になる前にはこんなのがありますよね。こういう大きいスポンジのやつから《フィンガー・ボックス》になっていくんですね。材料をたくさんもらったから、というところから。

柿沼:スポンジって、そんな大きなスポンジだったんですか。

靉嘔:なんかでっかいスポンジなんですよね、この部屋ぐらいでっかい。スポンジは端を落とすんですね、硬いから。端を落とした真ん中は向こうが取って商売するんでしょうけども。片面は硬いんですよ。片面は切ったとこで。そういうものだったんです、僕がもらったものは。

ヤリタ:カステラの端切れみたいな。

靉嘔:それで1年間ぐらい仕事をしたんです。体が入る小屋とか部屋とかね。

柿沼:ああ、それがそうなったんですか。

靉嘔:それがいろいろ評判になったんですよ、「変なことするやつがいる」って。

ヤリタ:アートはいっぱいあっても、音楽はあっても、触るっていう感覚の、驚かせたアーティストは靉嘔さんが初めてですよね。

靉嘔:初めてですよ。初めてです。

ヤリタ:《フィンガー・ボックス》、面白いですよね。うっかりこうやって画鋲で血が出たとかってトラブル、ないんですか。

靉嘔:まあいろいろあったんですけども。とにかく《フィンガー・ボックス》も作って。僕は木工所を持ってたから、それで何でも作れたんですよね。作りたかったから作って喜んでただけの話で、売れたわけじゃないんだけども。

ヤリタ:《フィンガー・ボックス》が入ってる大きい箱だってみんなきれいだし、Ay-Oの焼き印の入っているのも素敵ですよね。

靉嘔:とにかく触覚がないんですけどね。僕が最初に何かするっていうのは、とにかくどうしていいか分からないわけですよね。触覚はどうしたらいいかって、そこからやるんです、触覚は何かということをね。とにかくものにはみんな触覚がある。

ヤリタ:そうですね。触ると冷たいとか熱いとか、硬いとか軟らかいとか。

靉嘔:そういうコレクションしなきゃいけないというので、そういうコレクションを始めたんです。

ヤリタ:触覚を追求したということですね。

柿沼:ジョン・ケージ(John Cage)の『Notations』(Something Else Press、1969年)という本の中に靉嘔さんのタクタイルリストというのが入っているんですけど。これは砂とかミンクとか水とか書いてあるんですけど、これは触覚でみんな違うものですよね。これはどういうことで作られたんですか。

靉嘔:僕が最初にするんだから、何かきちんとしたことをしなきゃいけないわけでしょ。だからどうしたらいいかったら、まずリストを作ることだよね。

ヤリタ:触覚をリストアップしたということですね、触覚の感覚を呼び起こすものを。

靉嘔:冷たいとか、硬いとか、そういうリストをリストアップしなきゃいけないってんで。当然、オブジェクティヴなものが、また自分のものになっていくんだし。人間ってそういうものは非常に重要なもんで、どういうふうにかかわりあったからいいかということまで考えなきゃいけないことなんで。

柿沼:最初の《フィンガー・ボックス》は15個あったんですけれど。

靉嘔:いや、そんなことない。これ全部そうですよ。いっぱいあるんです。

柿沼:これ(タクタイルリスト)40個あるんですけども。

靉嘔:もっとある。100個ぐらいあるんですよ。ものは、みんなそうなの。

柿沼:そうですね。みんな触覚が違うから。ああ、そういうことですか。これはボックスにはしなかったわけですね、この40個というのは。

靉嘔:一つずつの箱でいろいろ違ったものはあることはあるんだけども、そういうセットみたいなふうに作ったのが《フィンガー・ボックス》ですね。タクタイルセット。

ヤリタ:セットもあるし、部屋の格好で。

柿沼:部屋のもある。

靉嘔:普通の人はそういうこともしないですよね。いろいろ持ってきて、そういうものを作って、セットにして、面白い面白いってやってただけだから。

柿沼:これは66年に作られています。

靉嘔:もっと前ですよ。63年ぐらいですか。

柿沼:早いですね。フルクサスが始まった頃ですね。

ヤリタ:さっき靉嘔さんがおっしゃっていたように、フルクサスというと日本では一種のスクールみたいに思われてるけど、そうじゃなくて。たぶん靉嘔さんが面白がってやっていた《フィンガー・ボックス》があったり、ドイツでナム・ジュン・パイク(Nam June Paik)がやっていることがあったりして、既成のアートのあり方に頼らず、やっぱりそれは戦前の文化に対するちょっと反発もあると思うんですけど。

靉嘔:それがね、変なことにね、僕みたいなアーティストがいるでしょ、パイクみたいな。そういうのがある時期、タケノコみたいに地球上に出るんですよね。

柿沼:面白いですねえ。

靉嘔:それがおかしいんだよね。人の真似したわけじゃないですよ。真似したわけじゃないんだけども、なんか面白いものができる。で、行ってみると「あ、これは面白い」ってんで、自分のようなもんだと思って、仲間だと思って、それをみんな宣伝してみたりやるんですよね。

柿沼:塩見(允枝子)さんも、フルクサスのことを知らないで《エンドレス・ボックス》(1963年)とかを日本で作ってらしたんですよね。それでパイクさんに「これはフルクサスだよ」と言われて、それでニューヨークに行くわけですね。だから不思議ですよね。

靉嘔:不思議ですね。それがどこにでもあるんですね。ソヴィエトの、共産国の連中もいたし。

柿沼:デンマークには(エリック・)アンデルセン(Eric Andersen)さんがいたし。

ヤリタ:オーソドックスなマーケット、経済的に美術の価値とかが決まった、お金と権威とアートとかがくっついたところに対して反発する人たちが、どこか新しいアートを生み出していったんですよね、たぶん。

靉嘔:そりゃみんなね、ドルをめざしていくんですからね。(笑)

ヤリタ:欲しいけど。

靉嘔:売れれば一番いいわけだけど、売れないから、ということはありますよね。

ヤリタ:それじゃあ《フィンガー・ボックス》を作っている頃に虹を描き始めているんですか。

靉嘔:そうか、まだそこまで行ってないんだ(笑)。

ヤリタ:すいません、虹が出てきたらいいなと思って。

靉嘔:とんでもない。

いろいろ分析するんですね。僕は絵描き出身なんですね。色をいろいろ知ってるし、知ってるって、知識はほかの人よりは多い。で、色について考える。そういうものを土台にして絵を描いてみようとか、そういうこともあるんですよ。で、描いてみたり。でも、そんなことする絵描きは僕しかいなかったですね。

ヤリタ:色を分析する。色というものの本質を考えていったときに、色は、光があたって色が見えるんですよね。

靉嘔:そうそう。そういうことはね、だいたい大学や美術学校に行けば勉強することですよね。みんな知ってることです。当たり前なことでね。僕が人よりちょっと知識があるといったらそういうことだけなんですが、みんな同じなんですよね。その頃、色についてのいろいろなものは一生懸命みんな探求したんですね。わりにコマーシャル・アーティストがそういうことをよく研究してました、色についてね。僕なんかはわりにそういうものを利用して。色についていろいろやって。色って、例えばまあ24色ありますよね。混ぜると48色。倍々にたくさん、永遠にあるわけです、色なんていうのは。またまとめるのも大変なんですよね。それをどういうようにしてまとめようと思うと、やっぱりコンセプトがいるんですね。で、「コンセプチュアル」というアイデアが出たわけですね。だからフルクサスのアーティストはコンセプチュアルのアイデアがあって。僕は色をうんとコンセプチュアルに考えてやったんだけども、普通はみんなそんなことはしなかったんですけどね。でもコンセプチュアルアートというのがその頃だんだん出だして、僕なんかの仲間で、アートはコンセプチュアルアートだ、コンセプトだ、コンセプトを追求するのがアートだ、と言うやつがいていろいろだったんですけども。で、コンセプチュアルアートが流行ったんです。だからそれが流行った後、僕なんか「神様」になるわけだ(笑)。

ヤリタ:最初に色のコンセプトを考えた。

靉嘔:色だけじゃなくて、コンセプチュアルなものという。

柿沼:色を、配色を決めるときにサイコロを使われたとおっしゃっているんですけど、どうですか。

靉嘔:そういうことはありますよ。何にするかということは、とにかくサイコロでもなんでも。割り箸にナンバーを書いて。筮竹。

柿沼:占いに使う筮竹のように。

靉嘔:抜いてきて色を決めるということは。あそこにある、正面にあるやつがそうですね。

柿沼:そうすると色の配色がああいうふうじゃなくて、バラバラになりませんか。

靉嘔:バラバラですよ。

柿沼:その後、例えばコンピューターを使うとかはされているんですか。そういうことはされてない?

靉嘔:コンピューターを使うほどのこともないんですよね。

柿沼:そうか。いや、ジョン・ケージは使ってるので。『易経』をコンピューター化して音の配列を決めるようなことをしてるんですけど、そこまではされてないですか。

靉嘔:何を選ぶかというと、サイコロで選ぶという方法があるでしょ。みんな僕の友だちはね、アメリカ人だけども『易経』の本を読んでるんだよね。僕がフランスに行ったら、ジョージ・ブレクト(George Brecht)とロベルト・フィロー(Robert Fillou)が一緒に住んでたのね。そして一生懸命『易経』の本を読んでるんだね。「なんでこんなもの読んでるの」って言ったら、「これはすごい本なんだ」って。すごい本だって、こんなもんは占いの本で。

ヤリタ:日本人からするとね。

靉嘔:でもよく考えるとやっぱり面白いんですよね、『易経』って。アメリカ人よりも日本人は『易経』が読めるわけですからね、オリジナルに。それを読んで、僕なんかすぐ仕事に使うようになったね。

ヤリタ:いろんなものが要素で組み合わさってきますね。虹も、虹というのは光を……

靉嘔:僕は、色は虹だと、スペクトル。人間が考えたのはスペクトル、スペクトルの色というので、赤から紫まで段階があって紫になるんです。そういうスペクトルなんだけども。それはまあ色彩学だけど、それを一生懸命追求すれば、細かく細かくやっていけばすぐ分かることですよね。それをどういうふうにものに使うかって。僕は、描いてやるよりも考えてやるほうが得意だったんですよね。ピカソは、ある時は、5年ぐらいですけども、ブルーの絵ばっかり描いたでしょ。

柿沼:青の時代。

靉嘔:青の時代、ピンクの時代とね。青はあんまり売れなかったけど、ピンクの時代になったら売れるようになったんですね。そうするとまた青の時代が売れるようになって。ピカソが売れたのはそれだけなんですよ。そんな大して売れてないんですよ。

柿沼:そうなんですか。

ヤリタ:若い頃はね。靉嘔さんは、可視光線の七色、虹の七色をいろんな方法でやられてますよね。例えば色を徹底的に細かく、192色までですか、分けられたり。

靉嘔:「にいよん、よんぱく、くんろく、いっくに」ですね。麻雀の点数ですよ。24、48、96、192。そこまでは実際に僕は仕事をしてみて作れるわけですよ。ある時は2年ぐらいそればっかりやってましたね。192グラデーションの絵を、なんてことはない、毎日1色ずつ塗るわけです。

ヤリタ:隣と混じらないように。乾かないと次を塗れないですもんね。

靉嘔:馬鹿みたいなことだけども。

ヤリタ:それも追求ですよね。

靉嘔:でもね、やってみなきゃだめなんだよね。理屈ではだめなんですよ。普通の人はやらないんですよね。考えは一緒ぐらいなんだけども、実際にやってみないとだめなんですよ。やってみるとまた新しい違う発見があるんですね。僕はやったんですね、実際に。192色の絵を描いてるとね、酔っぱらえないですよね。

柿沼:そうですか。

靉嘔:酔っぱらうと、二日酔いではだめですね。だから二日酔いしないように。

柿沼:体調に気をつけて。それぐらい研ぎ澄ました感覚でないと色の違いは出せないということですか。

靉嘔:24色なら簡単ですよ。48色、96色ぐらいなら。でも「いっくに」になるとほとんど違いがなくなる。前の日の絵の具が基準ですから、段階をやったら次の段階がなくなっちゃうというので、きちんと二日酔いをせずにやらなきゃダメですね(笑)。

柿沼:私は美術のことはよく分からないんですが、絵を描く段階から、今度は版画の方に移られましたけれども。

靉嘔:僕はね、初めからそれやってたんです。

柿沼:両方やっておられた。

靉嘔:みんな版画を馬鹿にするんですよね。版画は半分の画って書いて(半画)。

柿沼:半人前だと。

靉嘔:「そんな馬鹿な話はあるか。一枚の版画だって大きなキャンヴァスだって価値は同じだ」って。そこで僕は喧嘩っ早いからすぐ喧嘩するんですよ。

柿沼:面白いと思ったのは、絵師と、彫り師と摺り師というふうに、昔は、江戸の浮世絵なんかは分かれていたわけですね。分業でやっていて。靉嘔さんの場合も絵師でいらっしゃって、摺り師の方は別にいらっしゃるわけですよね。

靉嘔:います。今の版画家というのは、創作版画といって版画を作るでしょ。作ると次にまた眺めてて、また色を変えて。そういうふうに感覚的なんだね、みんな。僕は感覚を使わないんです。

柿沼:つまり一点物を作るということですね、それは。

靉嘔:いや、そんなことはないですよ。例えば192色の絵の具が作れるとしたら、192色を作る方法を考えるわけですね。それを考えて絵を描くわけですけども。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんは絵のコンセプトを考えているから、そのコンセプトを、シルクスクリーンとか版画とかっていう複製はわりと複製が作りやすいという、そういうことですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:自由に自分の感覚で作る人は、その版画というのは、わりかし正確に複製になっていかないけど、コンセプトは複製しやすいということでいいんですか。

靉嘔:それでいいです。正しいですよ。そう思います。普通アーティストってそんなことしないんですよね。「この絵はちょっとおかしい」って色を変えるわけです。僕は変えないんです。次の色この色、次の色はこの色って、全部24色で絵を描こうと思ったら24色作って全部塗れば終わりです。良くても悪くても終わりなんですね。

ヤリタ:だから理解されるんですよね、摺り師の方にも、コンセプトが。それは絵師の方の感覚ではなくて、靉嘔さんのコンセプトがそこに存在しているわけだから、そのコンセプトを摺り師も理解すればきちんとした複製ができるということですよね。摺りは、シルクスクリーンは助田憲亮さん、福井の。あの方とは長く。

靉嘔:今でも僕のを摺ってます。あと岡部(徳三)というのがいましてね。岡部は死んじゃったんですけど。

ヤリタ:有名な方ですね、岡部さんも。

柿沼:一つの作品をどのくらい摺るんですか。

靉嘔:僕はずいぶん昔から、アメリカへ行く前から版画を摺ってて。初めは石版画、それからエッチング、木版はやらなかったんですけど、銅版画……

ヤリタ:福井の創美(創造美育協会)の関係の方々ですよね。シルクスクリーンとかたくさん(靉嘔さんの)作品を買った方々が、今、大野とかにたくさんいらして、みなさん家宝のようにすごい大事にしてますよね。地方にいらして、本物の美術にあまり出会う機会のない方も、エッチングとかシルクスクリーンがあることで靉嘔さんの本物の作品に触れることもできたし、その売上げが靉嘔さんのニューヨークの活動をたぶん支えたんだと思うんですけど。そういう相互の関係があったと理解していいんですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。絵は一点物じゃないですか。そうじゃなくて、たくさんできるっていうんで版画は安いっていうんだけども、そんなこともないんですよね。たくさんできた方がみんなに持ってもらえるわけで。1点作るよりも10点作れば安く売れる、買ってくれる人も多いんじゃないかということがありますよね。そういうものは非常に重要な考えだと思いますね。

柿沼:フルクサスのアーティストの方たちは、よくマルチプルでお作りになりましたけれども、それと版画と関係ありますか。

靉嘔:同じものですよ。マルチプルは同じことです。複数、複数性。

柿沼:複数作るということは、一点物じゃなくて、ということですよね。

靉嘔:はなからアートは否定しているわけですよね。

柿沼:オリジナル、一点物というのは否定してる。

靉嘔:否定してる。そうじゃないアート、ということになるんですね、やっぱり。それは、音楽家の友だちが多かったということがありますよね。音楽家は作曲するっていうでしょ。絵描きだって作曲はできるわけですから。で、やれば、スコアができて、2回も3回もそれを演奏する。これだって2回も3回も同じ絵が描けることになるわけで、版画が。今までのアート至上主義をやっぱり拒否することにはなるわね。

柿沼:音楽のことでちょっとお伺いしたいのですけれども。フルクサスでマチューナスに知り合われた後で、シュトックハウゼンの《オリジナーレ》という作品を演奏するといってもめましたよね。その時に靉嘔さんも、結局最終的には参加されているわけですよね。

靉嘔:それはパイクがね、パイクはドイツでシュトックハウゼンと一緒のとこで仕事をしてたんです。彼がニューヨークでシュトックの作品をやろうということになって始まったんだけども、シュトックハウゼンはやっぱり有名な人でしょ。有名な人だから戦争中……

柿沼:シュトックハウゼンが帝国主義者だといって批難する人たちがいたわけですね。

靉嘔:軍国主義者ね。

柿沼:それでデモがあったんですか。

靉嘔:アメリカ人で単純なのがいるんですよ、やっぱりね。でも実際にそうで、シュトックの、ナチに協力した時代のものを持ってきて論文にしたりして、「それはわれわれはしない」ってやって。

ヤリタ:アメリカは、共産主義的なものも好きでないし、ナチス的なものももちろん嫌いだから、ちょっとピリピリ、そういうこと嫌いな人がいますよね。

靉嘔:いやあ、有名になるとしょうがないんですよね。日本でもみんな有名になると、作曲家はやっぱり国を謳歌する曲を書いてくれと言われれば。

ヤリタ:愛国的な作品を。戦争に協力したと言われるんですよね。

靉嘔:そういうことですね。

ヤリタ:一時期どこの国もそういうことはありましたよね。

靉嘔:みんなそうですよ。有名になればなるほどね。いい作家ならよけいそうですよ。

ヤリタ:日本は、レオナール・フジタ(藤田嗣治)がやっぱり戦争画を描いたって。藤田さんは嫌になっちゃってもう日本に戻らなかったですよね、それが嫌で。

靉嘔:僕は知ってますよ。藤田さんはアメリカを通ってフランスへ戻ったんですけども。

ヤリタ:世界旅行をして行きましたね。

靉嘔:彼を呼んだ人を知ってるんです、アメリカへ、日本人で。それで大変だったんですけどね。

ヤリタ:《アッツ島玉砕》(1943年)なんかも、戦争の、べつに賛美しているわけじゃなくて、そこにいる人の苦しさを描いているにもかかわらずずいぶん批難されましたよね、藤田さんは。

靉嘔:べつに賛美しなくたって、そういうことで傷つけたやつはいるわけだし。

ヤリタ:後からだと何でも言えるんですけどね。

柿沼:その《オリジナーレ》に彫刻家の役で出るということになったんですか。

靉嘔:シュトックの《オリジナーレ》という曲を、パイクが「これやろう」と持ってきたんですね。初めから「靉嘔はこの役」っていうんで。それは、シュトックが奥さんに書いた、メリー・バウアーマイスター(Mary Bauermeister)というんですけど、メリーに書いた曲なんです。奥さんはアーティストなんです。マグネットを使うアーティストでね。

柿沼:「彫刻家の役で出ろ」と言われて。

靉嘔:彫刻家の役で出ろと言われて。そしたらジョージ・マチューナスがすぐ反対するわけですよ。僕はあんまり喧嘩するのが好きじゃないんで、そういう喧嘩は。で、しょうがないなと思って、「俺は出ないことにする」って一時出ないことにしてたんですね。

柿沼:どうして出ることになっちゃったんですか。

靉嘔:アラン・カプロー(Allan Kaprow)がそれをオーガナイズしたんですよ。オーガナイズするのは、監督するのは、パイクはカプローにあげた、やったんですよ。僕はカプローを知ってたから、カプローは僕に「あれをやることにする」って。僕はメリー・バウアーマイスターの役を。役たって僕の勝手な作品をそこでやればいいんで。

柿沼:ああ、それで歯磨きとかやったんですか。あと髭を剃る。

靉嘔:そうです。

柿沼:それは色と関係あるんですか。赤のときに髭を剃る、オレンジで歯磨きをする? 色と関係があるように。

靉嘔:まあまあ、そう、みんな細かく関係をつけるんですよね。要するに音楽というのは時間じゃないですか。時間は、色にすれば、赤・橙・黄・緑・青・藍・紫(せきとうおうりょくせいらんし)を時間に当てはめればいいだけじゃないですか。赤から順番にしていけば色が使えるわけですね。

柿沼:で、7色やった。

靉嘔:7色ということも、たくさんの色もありますけど、使えることになるわけですよ。そういうことで色を使って。

柿沼:それでその後、武満(徹)さんが《七つの丘の出来事》(1966年)という作品を作って。

靉嘔:それは違うんですよ。それはそのー……

柿沼:で、靉嘔さんに捧げてるんですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:2012年に東京都現代美術館で再演していますね。

靉嘔:良かったね、あれ。やれてよかったでしょ。

ヤリタ:良かったですよ。

柿沼:私は見逃しました。見られました?

ヤリタ:見ました。高橋アキさんももちろんおいでで。一柳(慧)さんとか有馬(純寿)さんとかみんな。寒川(晶子)さんとか。

靉嘔:良かったよね。

ヤリタ:あの空間で、吹き抜けの大きい空間だから、普通のコンサートホールとか講堂と違うので、丘という感じが。脚立がいっぱいあるんですけど、脚立が丘な感じもするし。

靉嘔:やる連中もみんな若い、僕なんかと同じような野心のある人が多くて。なんかちょっとやると反応をするんですよね。一番最後、飛び降りたんですよね。やめろ、あれやばい、ケガするから大変だって。飛び降りたんですよ!

ヤリタ:若い男子が。

柿沼:脚立から。

靉嘔:あの上に、玉の上に飛び降りたんですよ。あれ4~5メートルありますよね。

ヤリタ:手品の人も面白かったし。お花をむしった、花の香りもするし。武満さんの音楽だと思ったら全然違って、一種の総合芸術ですね。

柿沼:パフォーマンスですよね。

靉嘔:武満さんはそれをやりたかったんですよ。あの頃、何と言うのかな、ああいう音楽があったんですよね。

ヤリタ:わりと前衛的な現代音楽ですね。

靉嘔:何だったかな、名前は忘れたけど、まあそういうことをシュトックからやったんですよね。それを持ってきて日本でやるときにはいろんなものを使ってやりたいという。

ヤリタ:音もあって、視覚もあって、感覚……

柿沼:武満さんはシュトックハウゼンのその曲から影響を受けたんですか。そうじゃない?

靉嘔:そういうものはね、コンセプトなんですよ。コンセプトをやりたくてしょうがないわけです、新しいコンセプトを、みんな誰でも。だからやったんですね。

柿沼:直接影響を受けたとかではなくて、武満さんは武満さんで。

靉嘔:面白いことはやってみたいわけじゃないですか。影響を受けるとかそういうことじゃないですね。

ヤリタ:みんな似たような時代に生きてると、時代がそんなに違わないと、その人が思いつくんだけどたまたま似通ってることっていうのはあるんですよね。

靉嘔:それもまたやってみたいんですよね。

ヤリタ:ナム・ジュン・パイクのお話が出たので、パイクとの。靉嘔さんとパイクはどこから仲良くなったんですか。

靉嘔:僕はニューヨークにいてね、フルクサスの、日本語をしゃべるのは僕のとこへみんな来るんですよね。パイクは(ドイツから)僕のとこに最初に来てて。日本人もいろいろ来るからね。パイクもいろいろやるんで。そういうことですね。

ヤリタ:日本人で最初にニューヨークに行ったのは靉嘔さんだから、塩見さんも、斉藤(陽子)さんも、久保田(成子)さんもみんな靉嘔さんをとおしていろんな人とおつきあいができていくんですね。

靉嘔:そういうもんですね。日本の若手もみんな行ったんですよ、その時代ね。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんはパイクのチェロのこういうやつには出たことあるんですか。

靉嘔:シャーロット(・モーマン、Charlotte Moorman)のね。

柿沼:ヌードのときにチェロの役をされたのは靉嘔さんですか。

靉嘔:僕がヌードじゃなくて向こうがヌードですから(笑)。

柿沼:向こうがヌードで。靉嘔さんがチェロになったんですか、その時。

靉嘔:そうそう、こうやって。

ヤリタ:弦をこう持ってるわけですね。

靉嘔:シャーロットがこうやって弾くんですよ、こうやって。シャーロットのおっぱいの中に〓入って〓(笑)。

ヤリタ:幸せですね(笑)。

柿沼:それはすごいですね。写真には何も書いてないんですよ。これをやってる人が靉嘔さんだって書いてない。

靉嘔:あれはパイクが自分で作ったもんですから。シャーロットにやらせたわけだ。それが、いろいろ注文が来ると、あれも忙しいからね、“Ay-O, Help! Help! Help!”って来るんだよね。「何だ」「これやってくれ」って。

柿沼:わかりました。楽しいです。

ヤリタ:ほんと、ほんと。靉嘔さんとパイクさんも長年のおつきあいですもんね。靉嘔さんのお嬢さんの花子さんの推薦状もパイクが書いてくれたって。ねえ。

靉嘔:美術学校へ行くのにね。そしたら向こうの学校の生徒や先生がみんな見に来たって、どんなやつかって。

柿沼:それはどこの学校ですか。アメリカの?

靉嘔:アメリカですよ。どこか下町の、12丁目か13丁目にあってね、音楽の、それに。

ヤリタ:ナム・ジュン・パイクの推薦状を持ってたら、それだけでね。自分の憧れのアーティストがお知り合いだったら、「紹介してくれよ」って感じですよね。

柿沼:ベン・パターソンさんが70歳になったときに来られて、富士登山されましたよね。上まで行かなかったんですけど。その時バス観光をされているんですけど。昔、66年にバス観光というのをされていて、フルクサスが。

靉嘔:バスは、僕がチャーターしてバスをつくって、彼が下りてくるのを5号目まで行って待ってて、そこでフルクサスのパフォーマンスをしたということですね。

柿沼:途中で、青木ヶ原で突然降りてとおっしゃった。

靉嘔:途中でいろいろやるんですよ、フルクサスのこと。

ヤリタ:いくつか(何ケ所かで)降りましたよね。青木ヶ原はレインボー・ミュージック、こうやって。

靉嘔:ああいうこと年中するんですよ、僕なんか。だってただバス乗っても面白くないじゃないですか。

ヤリタ:もちろんいっぱいいろんなイヴェントをしながら行くんですけど。

柿沼:もともとは66年に秋山(邦晴)さんなんかと一緒にされてますけど。なぜ、バス観光をやるというアイデアはどこから来たんですか、そもそもは。

靉嘔:いろいろあって、一番いいのはと考えたんですよね。お客から金を取るにはバスを仕立てて、バス賃を払えというのが一つですね。まあそういうこと。いろいろあって。

柿沼:乗り物を使うというのは面白いアイデアだと思いますけど。

靉嘔:そうそう。何か変わったこと、バスで面白いことをいろいろやって。あの時は泉岳寺も行ったんですよ。あれは面白かったですよ、泉岳寺は。

柿沼:アメリカでもそういうことをされたんですか、何か乗り物を使ったものというのは。

靉嘔:アメリカでも……、やりましたよ。

柿沼:どういう乗り物ですか。ベニスではゴンドラを使ったというのはどこかで読んだことがあります。ゴンドラ・レインボー何とかというのを。よくそういうことはされていたわけですね、乗り物とか。

靉嘔:そうね、面白いことね。

ヤリタ:バスは面白いですよね。

靉嘔:でもシャーロットは泳げないんだよね。でも入っちゃったんだね。相当水飲んだな、あれね。泳げないのに入っちゃったですよ。すごいな、あれはやっぱり。

柿沼:あとニューヨークでマチューナスさんがビルを買って、みんなで共同で住もうと言われたというのを聞いたんですが。みんなで共同で買って、共同住宅みたいにしていたというのを聞いたのですが。

靉嘔:ニューヨークで、僕なんかのロフトはマチューナスが最初考えて、われわれが一緒になって買ったんですよね。オーガナイズをマチューナスがやったんで、マチューナスはビルの中で1つもらえるんですね、部屋を。一番下とか。それが彼の儲けなんだよね。それで3つか4つやったんですよ、方々ね。

柿沼:それでコミューンをつくるみたいな考え方が。

靉嘔:そういうものやってて、ジョージが見つけてきたんだね、1つの。それは競馬の、競馬ったってアメリカの競馬で、後ろに車を、こういう……

ヤリタ:トレーラーですか。

靉嘔:トレーラーみたいなもんですけど、それを付けた競馬があるんですよ。

ヤリタ:引馬ですね。荷車、馬車を引く。

靉嘔:ものすごくきれいなんだよね。ジョージはそこの持ち主のものを買ったんですね。ジョージは、前からもので儲けて、それ以外に儲ける方法がなくなったんで、それで買ったんだけども。

柿沼:それでみんなでビルを買って。

靉嘔:ジョージはみんなに売りたかったわけですね、ジョージも金ないから。

柿沼:靉嘔さんもそれを買われたんですか。

靉嘔:買わない。行ったら、これぐらいの小さい部屋がこのぐらいの川の間に建ってるんですよ。「俺、これ買うよ」とか言っただけの話で、買ったわけじゃないんだけども。そういうことで誰も買わなかったです。

ヤリタ:あらま(笑)!

靉嘔:一番いい方法は、ジョージに、ヨーコを呼んでこい、「ヨーコに買わせろ」と言ったんですよ。ヨーコは金あるからね。それで呼んだんだね。ジョージには何のことやらわけ分かんないんだよね。ビートルズがどのくらい力があるかなんてこと知らないんだよね、あの人もナイーヴな人でね。とにかくジョンとヨーコが行ったわけ。彼が買ったとこのどこかを売りつけようと思って。結局買わなかったんだけども。

柿沼:ジョージ・マチューナスはそういうことをして儲けようとしてたんですね。

靉嘔:後でマチューナスが僕に言うんだね。「靉嘔、すごかったよ。いっぱいジャーナリストがパーッと来てね」って。

柿沼:ヨーコさんとジョン・レノンが来たらそれはそうですよね。

靉嘔:あれも不思議な男でね。

ヤリタ:あんまり実感なかったんですね、きっと。

柿沼:ビートルズを知らないというのもすごいですね(笑)。ちょうどその頃、ジョン・ケージもストーニー・ポイントというところに共同の住宅を買ってたんですけど。

靉嘔:昔からね、そこに住んでた。

柿沼:そこは行かれたことありますか。

靉嘔:1度ぐらいありますよ。仲間のとこへ行ってね。あの連中、なんだかいろんなことしてね。キノコ狩りとかやるんですよ。

柿沼:一緒に参加されたんですか。

靉嘔:そう。

柿沼:楽しそうですね。

ヤリタ:一度見て見たかった、参加したかったなという気はします。

靉嘔:男と女と分かれてね、みんな泳ぐんだね。池があって、pond。みんな裸で泳ぐんだな。みんな写真撮ってきた。見つからないな、あの写真。

柿沼:どこか島を買われて、そこに移住しようとしたという話も聞いたんですが。

靉嘔:買わなかったんだけども、買うためにそこへ行ってね。

柿沼:靉嘔さんは行かれなかった。

靉嘔:行かなかった。ヨシ(ヨシマサ・ワダ、Yoshimasa Wada)は行ったんだね。1晩泊まったんです、その島ね、無人島ですから。どこに泊まったかしらないけど、とにかく泊まったんです。木陰でおしっこしたら、poison ivy(ツタウルシ)にかぶれちゃったんだよね。で、腫れちゃって。翌日ビーチで。

柿沼:冷やした(笑)。

靉嘔:ヨシとあれは誰だったかな……忘れちゃった……

柿沼:それはカリブ海の島ですよね、無人島は。ヨシ・ワダさんと、ジョー・ジョーンズ(Joe Jones)ですか。

靉嘔:違う、違う。もう一人、ニューヨークから帰ってそこの学校の先生になって。有名なとこですよ。

柿沼:ケン・フリードマン(Ken Friedman)じゃなくて?

靉嘔:違う。今でも、もうやってないかな、2台ハイヤーを学校が買ってくれて。2人いるんだって、ショーファー(chauffeur、おかかえ運転手)が。

柿沼:あと抽象はいけない、具体でいくんだという。抽象絵画ではなくて、アブストラクトはだめで、コンクリートでいくというふうに絵をされたわけですけれども、ミュージック・コンクレートにも興味があったとおっしゃっているんですけど、ニューヨークへ行く前に。黛(敏郎)さんがミュージカル・ソーを弾いてくれたとおっしゃっているんですけど、そのことは覚えていらっしゃいますか。オノ・ヨーコさんのロフトに行ったら黛さんがいて。ミュージカル・ソーってノコギリで弾く。

靉嘔:知ってます、知ってます。

柿沼:それで弾いてくれたとおっしゃっているんですけど、それはそうですか。

靉嘔:そうですよ。

柿沼:それは、ミュージック・コンクレートの興味でそういうのは聴かせてもらったというふうに。

靉嘔:楽器じゃない楽器を使って音楽をみんなでやるのはわりに流行ってて。

柿沼:それはニューヨークへ行く前からそういうことには興味があったとおっしゃっているんですけども。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:やっぱり人と違うことが好きというのは。

柿沼:いろんなことにご興味があったんですね。

靉嘔:そうですね。音楽でも一番新しい音楽に興味があるんですね。絵でも一番新しいものに興味がある。何でも一番新しいものに興味があるんですね。

ヤリタ:人と違う新しさというのは、人と違わないと新しくないから。

靉嘔:新しものずきですね。

ヤリタ:それはそういうことですよね。その新しいことを発掘するには、勘じゃなくてコンセプトだということですね、靉嘔さんの場合は。

靉嘔:それはいったい何かということを、やっぱりやってみないと分からないですね。やってみるのはいいことですな。

柿沼:あと、いろんなお食事を、ディナーを出されてますけれども、食べる作品。油で揚げたりされますよね、お札を揚げたり。

靉嘔:天ぷら?

柿沼:天ぷら。お札は食べたんですか。お札を油で揚げて。

靉嘔:おさつってサツマイモ?

ヤリタ:キャッシュ(笑)。

靉嘔:ああ、あれはドイツで僕がやったんですね、2、3回。ヨーロッパでね。ちょうど 5,000円ぐらいです、1枚のお札を、持ってたやつに揚げさせて、天ぷらを作らせて、そいつが食べたですよ。

柿沼:食べたんですか(笑)。

靉嘔:僕は食べなかった。

柿沼:それはどういうことでやられたんですか。

靉嘔:お札食べるって面白いじゃないですか。

柿沼:フルクサスはギャグだ、アートじゃなくてギャグだと言ってる人がいるんですが。

靉嘔:いいんじゃないですかね。

柿沼:それでいいですか。

靉嘔:いいですよ。

ヤリタ:そういう要素もあるってことですよね。目的を笑いにしてないんだけど、新規な目新しいもの、peculiarとかstrangeなものというのは、時には恐怖だったり、時には驚きだったり、時には笑いだったり、時にはほほえみだったり、いろんな感情がわき起こりますよね、観客は。だからフルクサスがやっていることは、最初は笑いじゃないんだけど、過程で笑いもたくさん発生するということですよね。

柿沼:面白いですよね。ユーモアというのはすごく感じられますね。

靉嘔:「ユーモアについて」。1週間ぐらいやったんですよ、あれ。

柿沼:講座をね。

靉嘔:志賀高原で。5、6人かな。7、8人そろったですかね。

ヤリタ:助田憲亮さんのとこで私も資料を見せてもらいました。

靉嘔:助田もいたね。

ヤリタ:詳しくあれでしたら、今度助田さんのところに。

柿沼:そうですね。あとお伺いしたいのは、フルクサスの、舌を出してるこれは、メキシコかなんかの古代のあれですね。

靉嘔:そうです。

柿沼:これは何なんですか、手というのは。

靉嘔:それはジョージがどこかで見っけてきた。印刷してあるんですよ、このぐらいに。で、方々に貼る。

柿沼:あと中国人が、小僧さんがお尻を出している絵がありますよね。これはどこから取ってこられたんですか。

靉嘔:それはどこですかね。それは知らないですねえ。

柿沼:これとこれとこの手が、フルクサスのシンボルみたいな。

靉嘔:あるとき成子がここに絵を描いたんですよ。

ヤリタ:ヴァギナペインティング。

靉嘔:ヴァギナエペインティングね。それなんじゃないですか。それの挿し絵なんじゃないですか。

柿沼:そうなんですか!

靉嘔:成子は何もしなかったけど、それだけしたんだよね。後で「おなか痛い、おなか痛い」って。痛いだろうねえ(笑)。

柿沼:ねえ。パイクさんが「やれ」って言ったらしいですね、それ。

靉嘔:まあそうでしょうね。

柿沼:成子さんなんだ、これ。

ヤリタ:なんか東洋趣味。ちょっとどこか東洋趣味な感じはしますけどね。

靉嘔:こんなのあったんですか。みんなよく見てますね。

ヤリタ:印刷物にはよく出てますね、これ。

柿沼:フルクサスというとその絵が出てくるので。あと、ジョージ・マチューナスはみなさんのためのお名前のデザインをしてますよね。これは塩見さんですけど。靉嘔さんのも素敵な、ね。あれはどういう意図でされたんですか、名前をデザインするというのは。

靉嘔:ジョージはデザイナーだからね、ああいうことやるのは好きなんだな。

柿沼:仲間内で、彼が全部デザインしてやろうとしたということですか。みんな素敵なデザインですよね。

ヤリタ:その名前だけでアートですよね。Ay-Oだけでもねえ、それでアートになっていると思いますね。

柿沼:あと今、フルクサスについて思われることはどういうことがありますか。これは言っておきたいというようなことがありましたら。フルクサスは何だったんでしょうか。

靉嘔:(笑)何だったんだろうねえ、フルクサスというのは。でも変なグループだよね。変なグループですよ。

柿沼:でも世界中に散らばっていて、でもみんな仲間意識がすごくあって、素敵なグループだと。

靉嘔:まあ、ね、仲間意識っても、なんかへんてこりんなもんですよ。

ヤリタ:なんとなくパイクの「Help!」じゃないですけど、ヘルプというのはお互いヘルプしあったということですよね。

靉嘔:まあね。

ヤリタ:ミラン・ク二ザック(ニザック、Milan Knizak)さんが。

靉嘔:さっきのはミランですよ。

ヤリタ:ああ、ミランさん。ミラン・ク二ザックさんが、出国して国に入れないときに靉嘔さんに。

靉嘔:「Help me!」って(笑)。

ヤリタ:電報を、世界各国の。

靉嘔:世界中に電報を打つんだ、あいつね。それを真似したやつがこのあいだいたね、フルクサスに。タクシードライバーをやってるフルクサスのメンバー。何と言うやつだっけ、知りません? 有名な人じゃなくて。タクシードライバーをやってるんですよ、ニューヨークで。それでメシ食ってる。

柿沼:今でもですか。

靉嘔:今でもそうでしょうね。稼ぐもんがなかったら。東京に来てね、僕の展覧会の時に来て、インタヴューさせてくれって。2日ぐらいつきあわされてね、インタヴューに。

ヤリタ:清澄庭園でインタヴューを。

靉嘔:あそこでやったんですよ。そこの下で。

柿沼:みんな仲良くて、ヘルプで助け合ってやってらっしゃるのが素敵だなと思いました。人の作品を演奏するじゃないですか、パフォーマンスで。その人その人、別々じゃなくて、みなが助け合っているというところが。

靉嘔:やっぱりね、アーティストの作品を認めれば友だちなんですよね。認めなきゃ友だちじゃないんですな。

柿沼:そうですか(笑)。

靉嘔:それはありましたね。

柿沼:認め合った者同士ではそうやって仲良く。

靉嘔:それは、パフォーマンスするのにも、「ああ、あの作品をやろう」ということなんだな。そうするとみんなやるわけですよ。話し合ったことなんかないんですよ。

(地震発生)

柿沼:あっ、地震です。

靉嘔:ほんとだ。この中入りゃいいですよ、危ないときは。

ヤリタ:大丈夫です。それほどじゃないです。震度3から4ぐらい。最近は千葉県沖とかも。

柿沼:この辺も多いかもしれないですね。

靉嘔:多いですよ。

ヤリタ:地盤が、ここはきっと海と、もともとの境目のところですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。向こう行くと海ですからね。

柿沼:あとヤリタさん、何かお聞きになりたいことがありましたら。

ヤリタ:靉嘔さんもたくさんのお友だちがいらして、いろんな人のお話を聞きましたけど、逆立ちする人っていうのはどんなだったんですか。逆立ちする人誰でしたっけ。逆立ちのがいるんですね。靉嘔さんの誕生日だから逆立ちしてくれるとかって。

靉嘔:僕の誕生日に逆立ちして写真を送ってくるという、そういう人。あれはね……兄貴がヨーコのオーガナイズしてましたよね(注:ジェフリー・ヘンドリックス(Geoffrey Hendricks)のこと)。

ヤリタ:ジョン・アンダーソン(Jon Anderson)がヨーコのオーガナイザー(マネージャー)ですよね、たぶん。

柿沼:ブレクトじゃなくて。

ヤリタ:ジョージ・ブレクトじゃなくて。

柿沼:ここにアーティストリストが出てるんですけど、出てきません。

ヤリタ:すいません、私も分かりません。

お金がなくても、フルクサスのアートってコンセプトがあればできますよね。ミラン・ク二ザックさんの、落ちてるもので、私たちなんべんもそれでネックレスを作ったりしましたけど。逆立ちするのもそうだけど。お金がなくても人と違うアイデアがあればそれにアートになるというとこが、ポップアートにしてる節もないわけじゃないけど。アル・ハンセン(Al Hansen)もそうですよね。アル・ハンセンも、タバコの吸い殻とかHershey’sの殻とか固めてこういうのを作ったりしてますよね。ああいうのもお金がなくてもできるアートで、面白いですよね。そういうのはみなさんコンセプト、あいつがこんなことやってたり、この人がこういうコンセプトをやったり。

靉嘔:コンセプトがはっきりしてますよね。そういうことでしょうね。

ヤリタ:そうするとみんな「いいアイデアだな」って、自分も新しいアイデアを出そうというふうに思うわけですよね。

靉嘔:そうですね。

ヤリタ:ハンセンというおじいちゃんも面白いですよね、使っているものが。アーティストって、キャンヴァスがあって、イーゼルがあって、油絵の具を。昔の、19世紀の絵描きさんって油絵の具が買えなくてみんな苦労したじゃないですか、パリのモンマルトルの下町とかで。だけど20世紀のアーティストたちは、お金がなくても拾ったもので首飾りを作って、タバコの吸い殻で何かを作るというところが、私はそれが20世紀らしくて好きだなと思ってますけど。

柿沼:そうですね。

ヤリタ:そこはアイデアであり、靉嘔さんのおっしゃる、アイデアをやるということですよね。

靉嘔:ひとつはね、お金をかけないアートというものに興味があるわけですね。絵の具をいくら厚塗りしたって、これ絵の具を塗ってる。

ヤリタ:物質という意味では物質ですよね。

靉嘔:そうですよ。チャージできないじゃないですか。まあそういうものですね。

柿沼:スポンジもただでいただいたわけですよね。それはひとつ重要な点かもしれませんね。

ヤリタ:20世紀の大量消費社会で身近にあるものが、アイデアひとつでアートになって、みんなの感覚を靉嘔さんの《フィンガー・ボックス》で呼び覚まして。そこが20世紀の新しい、フルクサスのみなさんがやってくださったことで。

柿沼:そうすると原点はやっぱり(マルセル・)デュシャン(Marcel Duchamp)でしょうか、もとになっているのは。ありものでやるとか、あるものを使って何かやるとか、アイデアだけで。

靉嘔:デュシャンの悪口言うわけじゃないけども、みんなそれぞれですわね。デュシャンだけじゃないですよね。だけどみんなデュシャン好きですよ。僕もデュシャンが好きだ。だからニューヨークに行ったんで。デュシャンがいたから行ったんですよ、僕はニューヨークに。

柿沼:会われているんですよね、ギャラリーで。

靉嘔:何回も会ってますよ。

柿沼:デュシャンはどんな人でしたか。

靉嘔:おじいさん(笑)。いいおじいさんでしたよ。

柿沼:その頃はね、もうね。

靉嘔:インテレクチュアルなおじいさんでしたね、ものすごくね。

柿沼:お伺いしなきゃいけないことはいっぱいあるんですけれども。いろんなことを体験されているので。いろんな人とお会いになっていらっしゃるし。いろいろ面白いことを体験されていると思いますけども。

もうひとつお伺いしていいでしょうか。ハプニングとイヴェントとどう違うというふうに思っていらっしゃいましたか。カプローはハプニングをやったんですけど、フルクサスの人たちはイヴェントと言ってましたよね。

靉嘔:ハプニングというのは1回きりのもんですよね。イヴェントは何回もできるという。コンセプトがそういう。というふうにわれわれは考えたんです、簡単にね。

柿沼:人によっては、カプローは。

靉嘔:いや、カプローはハプニングですよ。

柿沼:はい。フルクサスじゃないという人がいるんですが。

靉嘔:フルクサスではないですね。

柿沼:ないですか、やはり。

靉嘔:フルクサスより先の人ですので。

柿沼:かかわりはあったけれども、フルクサスではない。

靉嘔:ジョージ・マチューナスが「フルクサス(Fluxus)」と言ったんで、その前の人だよね、カプローは。

ヤリタ:マチューナスが名付けてるわけだからね。

柿沼:やっぱりそのへんは違うんですね。

ケージとは何回かお会いになっていらっしゃいますよね。

靉嘔:会いましたよ。

柿沼:何か覚えていらっしゃることはありますか。印象に残っていること。

靉嘔:覚えてますよ。でも何しゃべればいいのかね。

柿沼:そうですね(笑)。わかりました。どうでしょうか、あと。

ヤリタ:私はだいたい。

柿沼:どうもいろいろありがとうございました。とても面白く聞かせていただきました。

ヤリタ:ありがとうございました。

柿沼:本当はまたこういうイヴェントをやっていただきたいなと思っているんですけど、このあいだのような。これはこのあいだの東京都現代美術館のプログラムです。「Viva! フルクサス」。

靉嘔:「Viva! フルクサス」。

柿沼:最後の、みなさんでやったものですけれども。

ヤリタ:楽しかったですね。

《07th》を説明するイラスト画(靉謳筆)